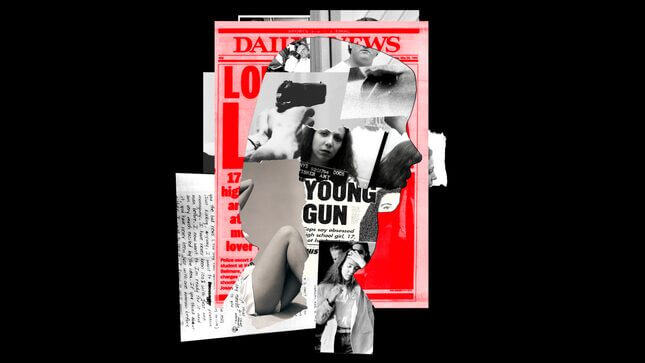

Illustration: Elena Scotti; Images: Getty

In 1996, when an 18-year-old Fiona Apple was wrapping up work on her seminal debut album, Tidal, executives from Sony Music asked her to write a “more obvious” first single. And so Apple, who wrote most of the album’s songs as a 16-year-old battling an eating disorder and PTSD following a sexual assault, sat down, slammed out a few angry chords, and in 45 minutes had composed the lyrics she correctly intuited the suits in the room wanted to hear: “I’ve been a bad, bad girl/I’ve been careless with a delicate man.” The music video for “Criminal,” which remains Apple’s biggest hit to date, opens on abandoned stuffed animals littered amongst empty beer bottles and a detritus of bodies taking a break from what seems to be an ongoing orgy. The entire video has the overexposed look of an illicit Polaroid.

While Apple was legally old enough by the time the video was filmed to record herself doing sex acts with as many consenting adults as she pleased, the video for “Criminal” is a clear reference to a popular narrative of the time: ravenously sexual, spoiled teenaged bad girls were making criminals of the adult men who couldn’t help but look at them. and becoming criminals themselves in the process. Many of the emerging female stars of the 1990s got their starts playing America’s collective, incredibly inappropriate Lolita fantasy: Drew Barrymore, Alyssa Milano, Alicia Silverstone. Even Britney Spears was ultimately a beneficiary and victim of the underage allure her marketing team built up around her. And perhaps nowhere was the decade’s fascination with “sexy” stories of minors spectacularly colliding with sexual maturity more fully on display than in the media feeding frenzy around the tale of 17-year-old Amy Fisher. Tabloids branded her the “Long Island Lolita” after she shot Mary Jo Buttafuoco, wife of 37-year-old Joey Buttafuoco, with whom Fisher had allegedly been having what the tabloids labeled an “affair” since she was 16.

For the tabloid press, Amy Fisher was better than fiction. Here was a real teenage girl the tabloids could paint as a Nabokov creation mixed with the 1956 Ed Wood-penned suburban nightmare The Violent Years, which featured an affluent, all-girl rape gang. But unlike the Lolitas these men dreamed up, Fisher was a real-life “bad girl,” and her story had all the attractions of pulpy entertainment—illicit teenage sex, prostitution, and violence—given a thin veneer of faux public interest, packaged as a fable about the dangers of spoiled girl children with too much freedom.

On May 19, 1992, 17-year-old Amy Fisher showed up on the doorstep of Mary Jo and Joey Buttafuoco’s suburban home in Massapequa, New York. Fisher, carrying a t-shirt from the body shop owned by the Buttafoucos, told Mary Jo Buttafuoco that her name was Anne Marie and that Joey Buttafuoco had been having an affair with her 16-year-old sister. “I think the idea of a 40-year-old man sleeping with a 16-year-old girl is disgusting,” Fisher reportedly told Mary Buttafuoco. Supposedly, she responded: “Well, he’s not 40 years old yet.”

Unconvinced by the t-shirt, after Fisher failed to satisfactorily answer questions about where she lived, Mary Jo Buttafuoco turned to go inside the house, and Amy Fisher shot her once in the head before fleeing in a car driven by a young male acquaintance. Buttafuoco was left permanently deaf by the gunshot wound, with lasting facial paralysis. Later on, when Buttafuoco made the talk show rounds to discuss an assault that was consumed by the public as both an outrageous tale of teenage immorality and a joke about the Long Island accents of those involved, even Mary Jo’s injuries became fodder for ridicule.

The shooting came at just the right time for New York City tabloids, desperate for another high-profile case after the recent conclusion to the trials of Carolyn Warmus, a 29-year-old Westchester schoolteacher convicted of murdering her ex-lover’s wife in what the news outlets described as a fit of obsessive jealousy. The murder itself seemed like a real-life retelling of the 1987 film Fatal Attraction, in which a professional woman, heartbroken at being discarded by her married partner, stalks and attempts to murder his family as punishment. But while Warmus’s two murder trials and eventual conviction spawned the typical tabloid frenzy for a murder deemed headline-worthy because a middle-class white lady did it—books, made-for-TV movies, the Snapped treatment—it was nothing compared to Amy Fisher. Warmus’s story only contained one lurid element, while Fisher’s contained multitudes. Privilege and suburban crime, sure, but also the secret ingredient for which it would soon become clear 1990s America was gluttonous: teenaged girls as criminals, driven to madness by their own outsized desire.

People magazine headlined its coverage of the assault and trial “Sex, Lies, and Videotape,” after a popular erotic thriller of the time; Maria Eftimides, one the feature’s authors, would later name her book on the subject Lethal Lolita: A True Story of Sex, Scandal, and Deadly Obsession. In other tabloids and even in more respectable outlets like Larry King Live, Fisher was branded the “Long Island Lolita.” Yet, despite readily slapping Fisher with the Lolita label, news coverage was loath to make any specific reference to the idea of statutory rape. A New York Times headline said Joey Buttafuoco had “admitted to sex” with Fisher rather than “been found guilty of one count of statutory rape,” which is what actually happened.

The story of a girl shepherded from “innocence” to experience by an older and eventually indifferent man is an old one. In Greek mythology, Leda was a beautiful young princess either “seduced” or raped by Zeus, depending on the telling. Io, another young princess, was turned to a cow as punishment for Zeus’s unasked-for affections. Danaë, hidden away by her father in order to protect her virginity, was discovered by Zeus anyway, and he impregnated her by turning himself into an, ahem, golden shower. In each of these stories, the difference between rape and seduction is negligible. But the common thread is that whether they are seduced or assaulted, each girl is left to sort through the consequences of Zeus’s actions long after the bigger figure loses interest, and the ways she handles the indifference makes her either a good girl or a bad one.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-