Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, AP)

It was a warm July day when Frau Troffea began to dance. She walked out of her home, into the narrow streets of Strasbourg, and began her frenzied steps. She danced uninterrupted for nearly a week, her feet swollen and bleeding. By the time she had tired of dancing, 34 of her neighbors had joined her; by the end of August, 400 of Strasbourg’s residents were dancing wildly through the streets.

It’s hard to say exactly why Frau Troffea started to dance or why her neighbors were so affected by her movements that they felt the need to join her. But one historian posits that the dance was precipitated by the psychological stresses of early 16th-century life. In 1517, the year before Frau Troffea began her dance, famine struck the town, and one contemporary chronicler simply called it “the bad year.” The bad year was a euphemism—it wasn’t just a year that was bad, it was many. Before the famine, Strasbourg had endured outbreaks of the English sweat, smallpox, and leprosy. Death loomed and disease was everywhere and nothing, not even the most fervent prayers, could stop either. Strasbourg’s institutions and its remaining citizens teetered on collapse. The residents had little to be joyful about, but they danced anyway, wild and jerking; their dancing clogged the streets, effectively paralyzing the work of the city.

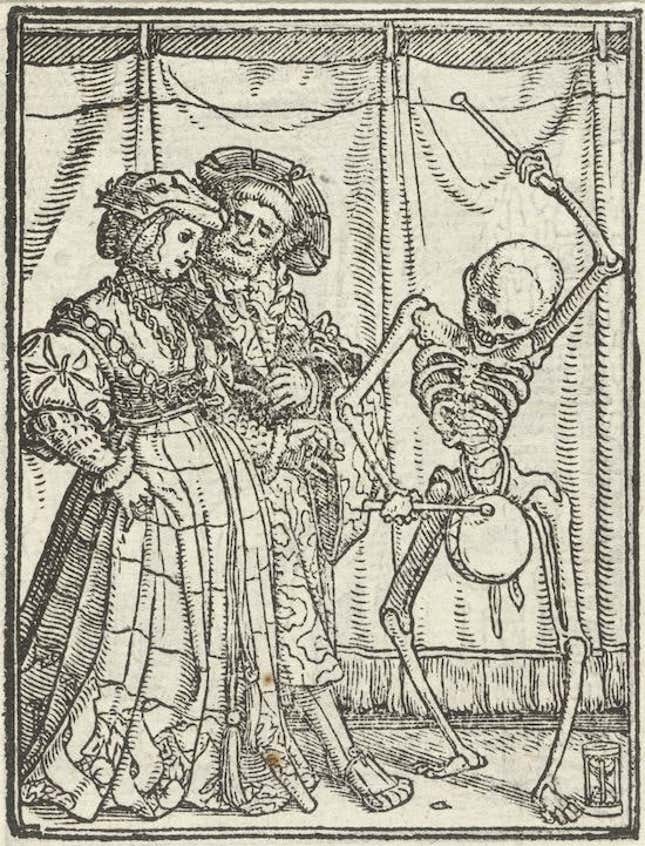

Worried for the crop and capital, the city’s noblemen and burghers brought in physicians to diagnose the dancers. They determined that the dancers suffered from “hot blood,” the cure for which was simply to keep dancing. The noblemen of Strasbourg emptied the guild halls and hired musicians to accompany the dancers and lure them from the city’s narrow streets. The dance continued up a nearby mountain and at a shrine that contained the holy images of the Virgin Mary and Saint Vitus. But not even the venerated faces of the saint could fully assuage the dancers, and their twirls and pirouettes continued. Then, by the end of the summer, the dance came to an inexplicable conclusion. Some of the dancers were healed, some dropped dead from exhaustion, and others simply went home.

Later, the Swiss physician Paracelsus named their dance Chorea Sancti Viti or St. Vitus Dance—chorea from the Greek “to dance in unison” and Saint Vitus, a martyred boy who cleaved to God as he was being boiled in a vat of oil by debauched Romans in the early second century. Vitus himself wasn’t much of a dancer, but on his feast day, worshippers danced before his statue. It was enough to cement the association between dance and the saint. Paracelsus believed that the dancers of Strasbourg were moved by “sympathy” and “imagination.” He attributed their dance primarily to melancholy and did not think those caught in the dance hysterical or mad. Rather, in keeping with his theory of movement, he believed simply that St. Vitus dance appeared “after a shock sometimes.”

The dance, he argued, was natural, like an earthquake—movement that needed to be expressed and could not be stopped, not some kind of divine punishment. It was only much later, after Saint Vitus became associated with the tics of the female hysteric, that Frau Troffea (who Paracelsus had a low opinion of, as he did with most women) was labeled as patient zero in an outbreak of dance mania, an episode of mass hysteria. But even as the dancers of Strasbourg were inevitably and retroactively transformed into an oddity of history and a morality tale about the “inexorable collapse of morals and manners,” the melancholy of the “bad year” that moved them was unshakable. Now it’s believed such actions are the result of a kind of radical empathy—a resistance of deadening affect in the face of such feeling.

Frau Troffea haunts me now. I think about the shape of “bad year” that so affected her that it pushed her into Strasbourg’s streets for weeks and about Frau Troffea’s neighbors, who were so moved by her dance that they too transgressed bodily order, abandoning their homes and mimicking her fitful choreography. It must have seemed to them, as the theater historian Kélina Gotman wrote, “that the world was coming to an end.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-