France Is Finally Reckoning With Decades of Shoulder-Shrugging Over Child Sexual Abuse

Latest

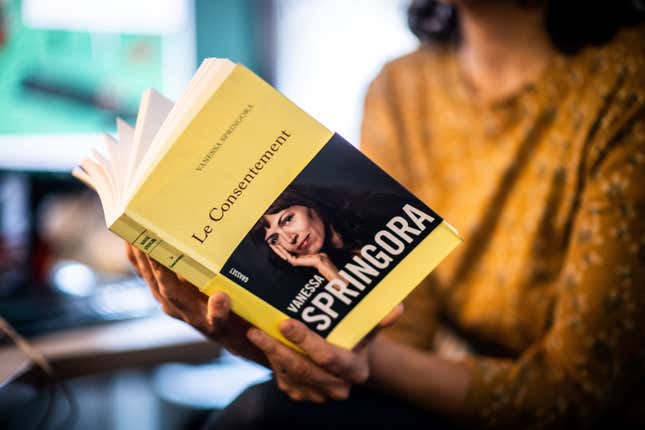

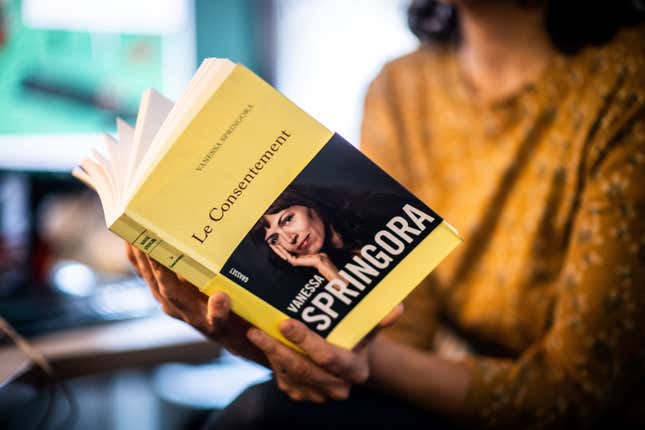

A woman’s book-length account of being molested at the age of 14 by a noted French literary figure has prompted a reckoning in the country over attitudes toward child sexual abuse. Last Thursday saw the publication of Vanessa Springora’s Le Consentement (or Consent), which details how the author was allegedly groomed into a quote-unquote “relationship” by celebrated writer Gabriel Matzneff, then 50, whom she calls a “predator.” That a book detailing such vile acts has sparked outrage in France isn’t surprising—except that its revelations are not new. Matzneff has long been vocal about, by the definition of United States law, sexually abusing children (in his own delusional terms: having sex with children).

Now, despite the previous widespread awareness of Matzneff’s writing about children, the high-profile book has suddenly prompted Paris prosecutors to launch an investigation and the French government to reconsider a writer’s allowance provided to him. It’s also caused some to scramble to excuse their previous joviality toward Matzneff. The New York Times reports, “The former host of France’s most famous literary television program struggled to explain why he and other guests—except, tellingly, the only non-French invitee—laughed with good humor at Mr. Matzneff’s preferences for minors.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-