From Riot Grrrl to Real Girl

Kathleen Hanna’s new memoir, Rebel Girl, gave me flashbacks to discovering my gender identity as an uncertain teenager, when I dug myself deep into Riot Grrrl, its burning messaging giving me a sense of control in my life.

Photo: Shutterstock In Depth

Most punk shows exist in damp, dark basements where bodies smash themselves into one violent, wriggling nucleus in the middle of the room. Though many spectators feed off this frenetic energy, letting the music get their hearts racing, my blood pumped with anxiety when I first started hanging around punk scenes as a teenager. And so I would watch the pit from the side, avoiding any errant fists or getting bodychecked by men twice my size.

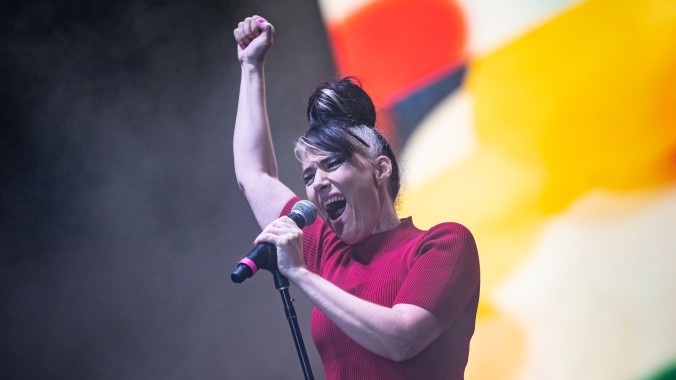

But I wasn’t afraid to lose myself in the crowd when I saw Bikini Kill a few years ago. When legendary frontwoman Kathleen Hanna performs, she claims the space that she occupies with a scorching scream. “Girls to the front,” she instructs at her shows, making sure anyone who has felt similarly small in a crowd can finally experience the liberation of a mosh pit, getting out all aggressions by jerking your body with abandon.

I was in the crowd surrounded by my best girlfriends at their first show in Seattle in over 20 years, and we all screamed along to the band’s introductory manifesto: “We’re Bikini Kill and we want revolution, girl style now!” I filled my lungs and threw myself into the pit of fellow Riot Grrrls, making up for all the crowds I was pushed out of.

In her new memoir, Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk, Hanna documents her journey from the evergreen mist of the Pacific Northwest to fronting the legendary bands Bikini Kill, Le Tigre, and The Julie Ruin. From the stage and on record, Hanna’s lyrics are determined and radical, amplifying messages about abortion rights, domestic violence, rape, and sex work set to urgent punk rock, making feminist messaging accessible to anyone who will listen.

While attending Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, Hanna’s art form of choice was spoken word poetry. A meeting with the revolutionary author Kathy Acker at a lecture encouraged her to start a band if she wanted to be heard; “Most people go out and smoke when someone gets up to do spoken word, but people want to see bands” Acker told Hanna. She discusses the hostility she faced when getting involved in the Olympia punk scene, mostly from enraged men who would taunt the band with threats of violence which would only grow in severity as her career grew, but Hanna’s reputation still stands strong today because she never let her adversaries shut her up.

The stories told in Rebel Girl are full of vivid detail that show she always had the glittering aura of a performer. Hanna writes tenderly about first discovering how to sing, with much more care and reverence for the skill of musicianship than one would expect from a scrappy punk vocalist:

Almost as an experiment, I opened my mouth and sang “Away in a Manger” as loud as I could. I walked towards the wall and noticed how the sound bounced off of it and got even louder. Hearing my voice bouncing back at me was like watching light refracting off a mirror. A mirror I could finally see my whole self in. If there were words my body could have said, they would have been “Right now is perfect. Right now, nothing bad is happening.”

Later on, Hanna writes about early Bikini Kill tours, when she finally felt that she was doing what she was meant to do, or how her friendship with Kurt Cobain and an off-the-cuff joke she made ended up becoming the title for one of the most famous songs in history, “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Then at the turn of a page, these charming anecdotes mutate into stories of trauma and survival, from the barrage of sexually inappropriate comments from her father while growing up or her dissociation while being assaulted by a close personal friend. But that is the point of Rebel Girl; not to gloss over events or to paint a happy picture, but to give an intimate look at how she became one of the most unwavering political voices in music.

The memoir gave me a newfound appreciation for Hanna as a writer; she stretches her prose out into poetic phrases, whereas her lyrics are typically terse, assertive, and urgent. This is not to knock the brusqueness of Hanna’s lyricism, of course, which was always a crucial part of her appeal. Even 15 years removed from the heyday of the Riot Grrrl era, I remember how “Rebel Girl” broke my consciousness wide open in middle school, and showed me a model of femininity in which I could picture myself. “That girl thinks she’s the queen of the neighborhood,” Hanna sneers over a guerilla drum march. Whether “that girl” was a friend, a crush, an extension of herself, or an amalgamation of them all, I knew I wanted to be her. After all, who wouldn’t want to be the fearless muse Hanna proclaims as “the queen of my world”?

I dug myself deep into Riot Grrrl as an uncertain teenager, its burning messaging giving me a sense of control in my life. I would click through the Riot Grrrl Wikipedia page, discovering the shattering wail of Sleater Kinney and the low-fidelity riffs of Bratmobile, but Bikini Kill was the centerfold I always turned back to. I didn’t have the words to describe the discomfort I felt about being perceived as a boy my entire life, but discovering Kathleen Hanna’s music became a turning point for me. Maybe I couldn’t yet call myself a girl, but I had no issue proclaiming myself as a Riot Grrrl.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-