Amy Grant and the Crossover Album That Rocked Christian Music

Entertainment

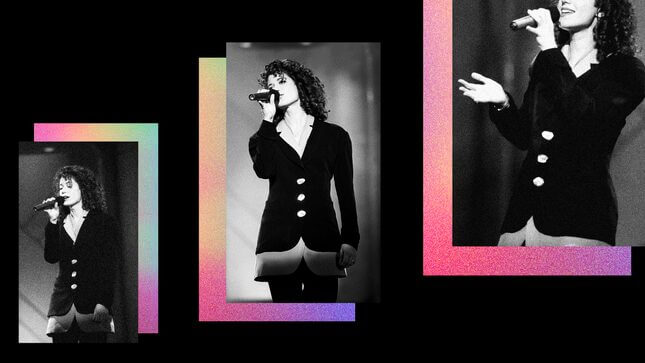

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, Shutterstock)

Contrary to what has previously and erroneously published on this website, there is such a thing as a single best track on Amy Grant’s 1992 album Home for Christmas. The answer is “Breath of Heaven” and anyone who even tries to bring other tracks into the discussion has never been tasked with singing “Breath of Heaven” at their church’s three-day-long Christmas production. Now, because I was a child upon its release and a mediocre singer on a good day, I never got my chance to sing that most blessed song but I was at the many, many rehearsals where one of our church soloists was working her best to nail the husky Amy Grant voice needed to successfully transmute all of the emotions contained within “Breath of Heaven” to the congregation.

Holiday music aside, Amy Grant was a looming figure in my mother’s high-tech stereo, which held a whopping three CDs at once, allowing her to rotate with ease between Amy Grant, Kirk Franklin, Jaci Velasquez, The Winans family, and any other Christian artist that had a stream of Godly bops with which to fill our home. Grant, who released her first self-titled album in 1977, was a gold mine of contemporary Christian music designed for cool Christian folk who wanted to jam in their cars to some sick guitar riffs but also praise Jesus, a stone that killed two birds.

The magic of Grant, and other white artists like her who didn’t have the vocal power needed to do straight-up gospel, is that she was able to bridge a cultural gap between highly conservative Christians who weren’t listening to Top 40 songs (because God) and what we in the Christian community used to call “sippin’ saints.” Sippin’ saints were a very specific breed of Christians, often non-denominational protestants, whose favorite bible story is the one where Jesus turns water into wine because that story allowed them to consume alcohol in moderation—hence the sippin’. Amy Grant’s upbeat Jesus tunes gave sippin’ saints something to sway back and forth to while also rescuing the ears of conservatives from the monotony of hymnals. How many times can one really rock out to choral “Amazing Grace” without needing to spice it up with an acoustic version of that song, whether from Grant herself or Chris Tomlin, if you really wanted to jam for Jesus.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-