Fire Island Is Both a Paradise and a Contradiction

Jack Parlett's irresistable new book and the Fire Island movie lay bare the complexities of this queer summer haven.

BooksEntertainment

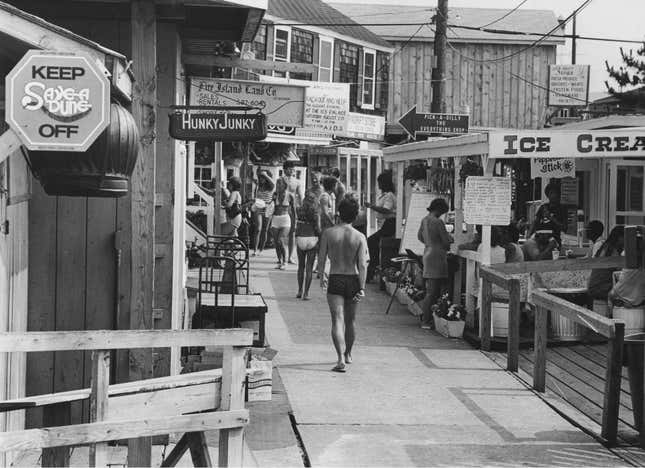

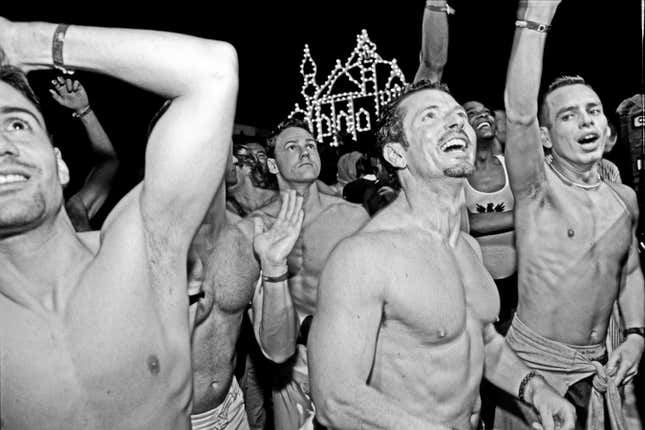

The first rule of Fire Island is: You talk about Fire Island—a lot. Hulu’s recent movie, directed by Andrew Ahn, goes down as easy as a vodka soda on an 85-degree summer day, which makes the plate-spinning of the screenplay by Joel Kim Booster (who also stars in the movie) that much more impressive. Not only does the film graft modern gay proto-romance (that is, the period of time when two people are kind to each other before fucking) onto the template of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice, it explains to the uninitiated the draw of the titular strip of land off New York’s Long Island that is home to several small resort towns. The film takes place in two such towns known for their predominantly queer populations, rich cultural history, and contemporary decadence: Cherry Grove and the Fire Island Pines.

For many who go and/or aspire to do so, Fire Island is synonymous with these two towns, much like how Kleenex has come to describe facial tissue. Booster’s script likewise accounts for the conflicting takes that fling back and forth among people with strong opinions about Fire Island. According to the character he plays, Noah, Fire Island is “like gay Disney World: fun for the whole family,” and “literally…paradise.” Noah says this despite admitting to feeling mostly invisible to the island’s larger white, gay population as an Asian-American. Other characters are less charitable with their ambivalence: “This place is so toxic,” says Howie (Bowen Yang). Yet he, Noah, and a few of their friends return, year after year, like flies to top-shelf shit. “This place is like a playground for superficial, vapid morons,” says Will (Conrad Ricamora). He’s later surprised to encounter Noah engrossed in an Alice Munro story collection.

“People don’t understand that it’s possible to believe in a thing and ridicule it at the same time,” might as well be the movie’s credo, but it was actually said some 75 years ago by gay poet W. H. Auden, who summered on the island and wrote about it at length. Fire Island looks like heaven and can feel like hell. It can also be affirming, a haven that justifies its own existence as a queer hub even in the age of marriage equality, even when the options for people to live out and proud have expanded considerably since the ‘30s, when queer populations first started making Cherry Grove their own.

That Auden quote originally appeared in a 1947 issue of Time and is reprinted in a new book by Jack Parlett called Fire Island: A Century in the Life of an American Paradise. If Booster’s task of conveying the Fire Island experience while weaving a coherent and frothy romance was a clear challenge, Parlett’s task of compacting about 100 years of cultural history into a slim volume would seem nearly impossible. That is, if he weren’t such a deft storyteller. His book breezes by with beach-read ease but is packed with enough facts, theories, and anecdotes to inspire weeks’ worth of dinner conversations. Though they’re very different projects with very different audiences and hang-ups, both the Fire Island movie and Fire Island book demystify the Fire Island experience and repeatedly uncover ambivalence, as if the only way to really understand a place is to see its complexities laid bare.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-