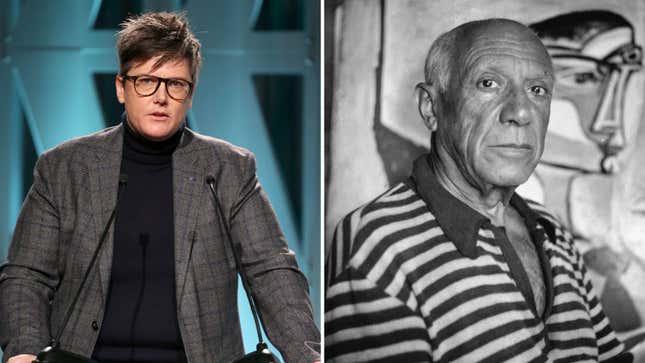

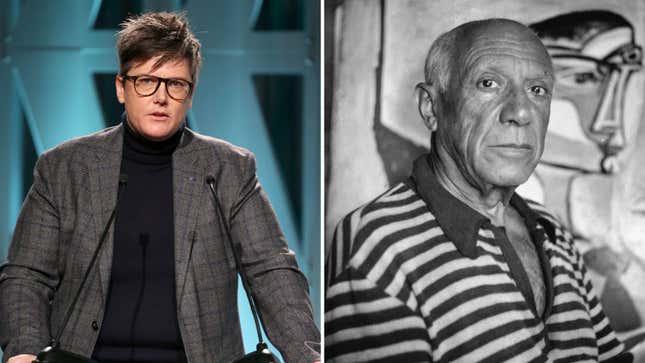

Hannah Gadsby’s ‘Pablo-matic’ Is Not the Feminist Achievement It Wants to Be

Gadsby skewered Picasso in their 2018 special Nanette—but their new art exhibit doesn't convey anger, humor, or frankly anything that deep.

Entertainment

The first works to greet you in Brooklyn Museum’s “It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby”—an exhibition co-curated by the Australian comedian that reckons with the painter’s tremendous and tricky legacy 50 years after his death—are by artists Philip Pearlstein and the Guerrilla Girls. Pearlstein’s melancholy portrait of feminist art historian Linda Nochlin and her husband sitting beside one another, avoiding eye contact, is framed beside a gallery wall of Guerrilla Girls pieces, including the iconically critical “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” Together, they give off an air of frustration and anger, presumably directed at, you guessed it, Pablo Picasso.

There’s a lot to be angry about regarding the titanic figure: his womanizing, his misogyny, the overblown genius and cultural appropriation. Gadsby’s 2018 Netflix special, the discourse battleground Nanette, reamed Picasso’s legacy, squaring it against his moral failings as an individual. In it, Gadsby focused in on his sexual relationship (when he was 42 years old and married) with an underage girl, Marie-Thérèse Walter, who he said was in her prime during their dalliance. In righteous anger, Gadsby revealed at the culmination of the special that they’d been brutally raped at a similar age, and explained how bleak it is to think of a girl at that age as “in their prime.”

When I first watched Nanette, I was struck by Gadsby’s anger. “I don’t like Picasso. I fucking hate him. I really… I just… He’s rotten in the face cavity. I hate Picasso! I hate him!” they say, before explaining that they’re often met with rebuttals about the brilliance of Cubism when they express said anger. The special accurately captured the absurdity of lauding a man’s supposed ingenuity at the expense of other people’s autonomy and perceptions. In 2018, at the height of the MeToo movement, pointing out that paradox felt powerful in and of itself.

But it is now 2023 and the understanding that patriarchy is dominantly misguiding and that systems of power uphold and even promote abusers is baseline knowledge for most people buying a ticket to a retrospective of Picasso 50 years after his death at the Brooklyn Museum. I know that when I hear those ideas presented, I find myself either wanting to or actually saying, “And?” I’d expected Gadsby’s co-curated show, silly pun of a name be damned, to answer that “and?” It doesn’t. The wide-spread panning of this show across the art world corroborates my hunch that others didn’t get an answer either.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-