Hospital CEO Says Black Doctor Who Died of Covid-19 Was 'Complex,' 'Intimidating'—Not Mistreated

Latest

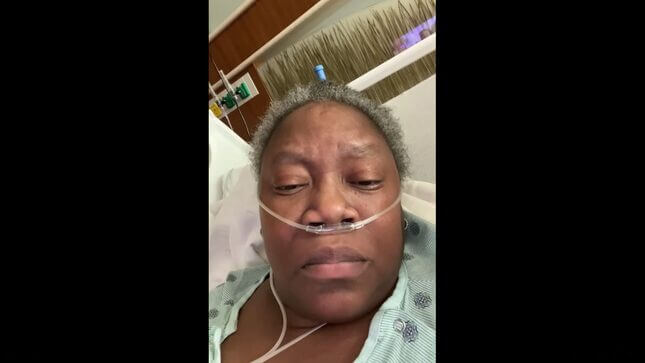

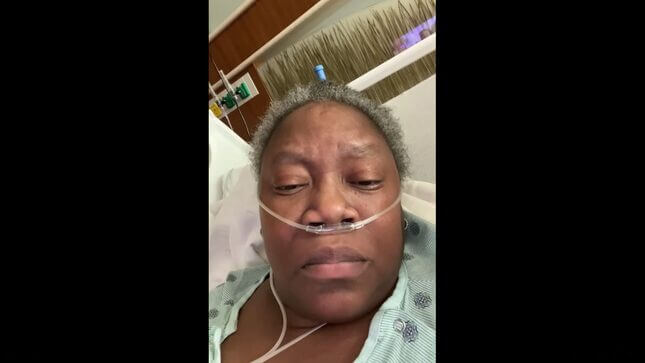

“This is how Black people get killed,” Dr. Susan Moore told her Facebook followers in a video she uploaded in early December. She was laying in a hospital bed with oxygen tubes in her nostrils, eyes watering. “When you send them home and they don’t know how to fight for themselves.”

Dr. Moore, 52, was detailing the care she received at an Indianapolis hospital following a covid-19 diagnosis, accusing the facility of treating her poorly and downplaying her symptoms because she was Black. Dr. Moore’s white doctor suggested she be discharged from the hospital earlier than she was comfortable with, considering she was still very short of breath and was in immense pain. She suggested various treatments and only received them after ample pushback from the medical staff and patient services. After some improvement, Dr. Moore was officially discharged. Days later, she was dead.

Now, the hospital’s CEO is suggesting that racism wasn’t the problem, but rather Moore’s attitude. In a statement, Dennis Murphy, CEO of Indiana University North Hospital, ensured that there would be an investigation into Dr. Moore’s claims, but also went to great lengths to defend his staff to the point of making Dr. Moore’s sound like a difficult patient to work with (emphasis ours):

It hurt me personally to see a patient reach out via social media because they felt their care was inadequate and their personal needs were not being heard. I also saw several human perspectives in the story she told – that of physicians who were trying to manage the care of a complex patient in the midst of a pandemic crisis where the medical evidence on specific treatments continues to be debated in medical journals and in the lay press. And the perspective of a nursing team trying to manage a set of critically ill patients in need of care who may have been intimidated by a knowledgeable patient who was using social media to voice her concerns and critique the care they were delivering. All of these perspectives comprise a complex picture. At the end of the day, I am left with the image of a distressed patient who was a member of our own profession—one we all hold dear and that exists to help serve and better the lives of others. These factors make this loss doubly distressing.

Calling Dr. Moore “complex” comes across as a polite way of calling her a bitch, which is alarming enough. But perhaps worse was Murphy’s decision to refer to Dr. Moore as an “intimidating” presence. If he intended to take the stink of racism off his hospital, that certainly didn’t do the trick.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-