If You're Going to Make a Star-Studded, Semi-Fictional Podcast About a Real Man's Murder, Maybe Contact His Family First

Politics

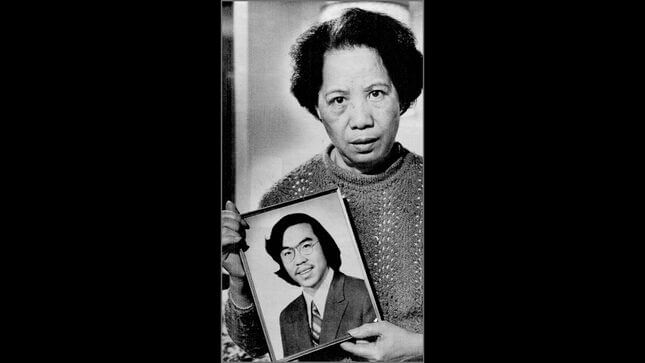

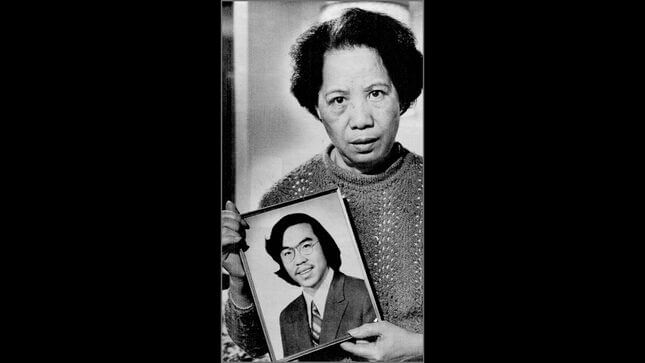

The podcast Hold Still, Vincent, a dramatization of the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, has been pulled after criticism from Chin’s family as well as journalist Helen Zia, whose activist work following Chin’s racially motivated murder helped bring federal civil rights charges against Chin’s assailants. NBC News reports that neither the Chin family nor Zia were “consulted about the project.”

From NBC News:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-