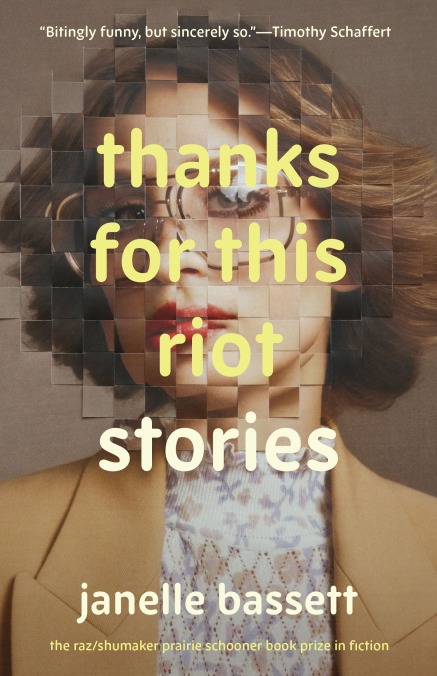

In ‘Thanks For This Riot,’ Janelle Bassett Gives Us Brilliant Observations of Rural Women

The debut short story collection is sadly funny, oddly dark, distinctly feminist, with a thrumming undercurrent of Christianity—it's giving a bit Flannery O'Connor.

BooksEntertainment

While reading Janelle Bassett’s debut story collection, Thanks For This Riot, I kept asking myself: Do these stories feel like they’re directed by Todd Haynes or Todd Solondz? I hate to even reference two male directors when talking about a book that is so consistently from the perspective of a very strange and powerful woman, but I couldn’t stop thinking, “Which of the Todds are being summoned?”

I should be referencing Lorrie Moore, or even Miranda July, or no one at all, because there is also something so idiosyncratic about this book, each story clearly born from the mind of an outsider mother from the Ozarks. I am thinking of the Todds though, because in the opening story, a teenage girl’s mother has instilled in her daughter an elaborate paranoia of being kidnapped by strangers. In this story, sitting alone at a local fun park, wearing a spaghetti-strap tank top for the first time, the girl requests two tissues from a woman pushing a stroller, and places the tissues on each of her bare shoulders, “For warmth. For protection.” she says. It’s this private, odd, often dark depiction of womanhood that calls to mind the Todds. I hear Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995) in these stories, I hear Safe (1995). I also hear something very personal and brand new.

Janelle’s book won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize and, with its singular characters, inventiveness, and humanity, has all the beauty of a breakout collection. She’s an editor whose own work appears in The Offing, The Rumpus, and Smokelong Quarterly. She’s so good at sad humor, and a version of country feminism that reveals the complicated longing of rural women searching to free themselves from tradition. Each story offers a perverse view of pop culture from the perspective of someone who doesn’t quite have access to it, but there is also a loving profundity to the work.

There’s the story of a young woman who unexpectedly finds herself babysitting the daughter of two famous comedians. In another, a wife prepares for a medical procedure that will lower her expectations. In one of the final stories in the collection, “Full Stop,” a woman carpools to an abortion rights rally with a voice actress who may or may not be a conspiracy theorist. The whole book is laced with moments of unsettling irony, brilliant observations about the minds of modern Americans, and incredible compassion towards the misunderstood and marginal. Janelle and I talked about some of this, and where ideas for art come from.

Why do I feel like you grew up in a religious environment? I’m not just saying this because you’re from rural, southern Missouri, although there is something particularly Ozark about your point of view. There’s a sneaky undercurrent of Christianity in your stories. She’s giving a little Flannery O’Connor. What was the culture like there when you were growing up?

The culture was definitely Christian, conservative, and patriarchal, but I was not overly aware of this until I was a teenager—it was just the soup I was cooking in. As I got older, I sensed the hands of those confining values closing in around my neck. I felt judged, held back, reduced. I became sharp and angry. But I don’t think I could have articulated what, exactly, I was reacting to. It’s possible that a lot of the characters I write are the same. They are resisting the structures they’re inside and yet they wouldn’t be able to talk at length about what they’re up against. It’s more of a gut-level resistance than an intellectual one. Not a lot of rebuttals, just lots of sighing and grunting.

And I’m happy that I sound like an Ozarker!

Reading your book, I wondered, is this what they mean by “domestic fiction”? It’s awkward conversations. It’s a mismatched intimacy. It’s women washing dishes and thinking about suffering. Do you have a theme, as a writer, on purpose? Does any writer have a theme on purpose?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-