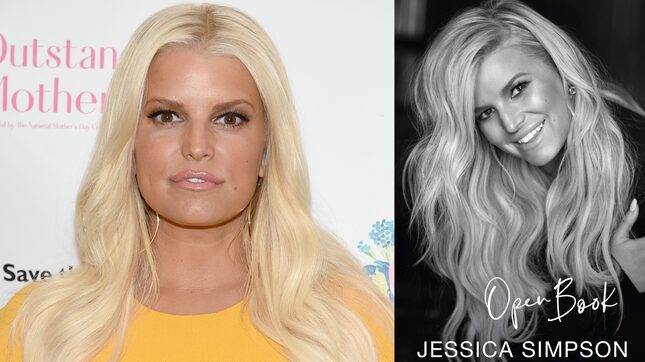

On the first page of Jessica Simpson’s 400-page memoir Open Book, she’s sitting in the passenger seat of a car, one “glittercup” (a bedazzled tumbler “filled with vodka and flavored Perrier”) in. It’s 2017, 7:30 in the morning, and she’s on her way to a Halloween assembly at her daughter Maxwell’s kindergarten. More than a compelling way to begin a memoir, the scene establishes its tone: Simpson is more transparent than she’s ever been, an actual open book when pop stars rarely are. In the past, her persona as the girl next door meant projecting that she was as embarrassing and mortal as the rest of us, but in Open Book, Simpson’s interior life is accessible and far more complex than her public performance as a relatable pop star. Take it with a grain of salt, but take it in.

As Simpson comes to terms with her alcoholism, she naturally revisits how she might have ended up there, recounting grade school bullying; a traumatic head injury during a car accident; and years-long sexual abuse by a family friend who was also abused in childhood, all images juxtaposed with her Baptist upbringing. Her unwavering faith exists throughout the text and is never interrogated except in one of the many damning sections about an emotionally manipulative John Mayer, who she says would treat every conversation like a battle of wits, to the point where she felt she could never be honest with him. Simpson spares no detail when describing her one-sided relationship with Mayer, and his repulsive treatment of her has been well-documented publicly, as in the famous 2010 Playboy story where he described her as “sexual napalm.” “Have you ever been with a girl who made you want to quit the rest of your life? Did you ever say, ‘I want to quit my life and just fuckin’ snort you?’” he told the publication. “‘If you charged me $10,000 to fuck you, I would start selling all my shit just to keep fucking you.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-