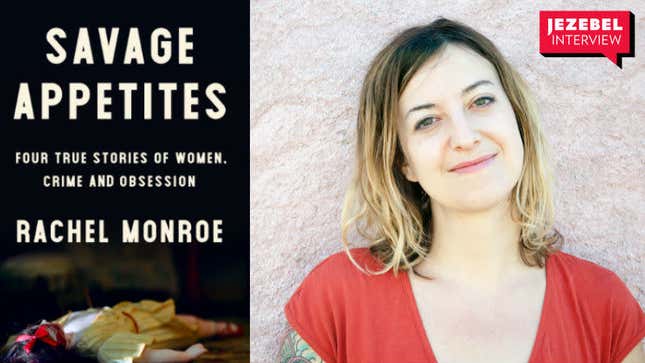

Rachel Monroe's Savage Appetites Examines the Complicated Reasons Women Love True Crime

BooksEntertainment

In Rachel Monroe’s book Savage Appetites, she describes something called a “crime funk.” It is when you might find yourself binge-watching Law & Order: SVU episodes back to back or when you’ve decided to read every Manson girl memoir after quickly gulping down Helter Skelter.

Like Monroe, I’ve often found myself in one crime funk after another, clicking through grotesque Wikipedia pages on serial killers or opening up multiple tabs for unsolved murders on the community Websleuths. Recently, I reminded my boyfriend that an idyllic California town we were vacationing in was the site of a famous murder, recounting the grisly details of the death as he tried to relax.

“It’s like that feeling of staying up really late and kind of zoning out and you’re half numb but also freaked out,” Monroe says. “I understand why people want to be in that half anxious, half numb place that I think going down a crime rabbit hole can take you.”

It’s easy to get trapped in a crime funk, but lately, it seems like it’s especially easy for women to live in one. From podcasts to Lifetime movies to conventions or Investigation Discovery marathons, true crime is largely consumed by women. In Savage Appetites, out August 20, Monroe dissects why women find themselves drawn to crime through the stories of four obsessive women who fulfill distinct archetypes: Frances Glessner Lee, the Detective, who created crime scene dollhouses to train homicide investigators and Alisa Statman, the Victim, a Manson-murder enthusiast who wormed her way into the Tate family to become an advocate for their daughter Sharon. There is also Lorri Davis, who fell in love with Damien Echols of the West Memphis Three, the book’s Defender, and the young wannabe mass murder Lindsay Souvannarath, who crushed on the Columbine murderers, is the aspiring Killer.

Monroe takes a sweeping, meta-approach to these stories, which go far beyond these women and the murders they’re drawn to and into the laws and policies they created. It’s a book about true crimes, but also how people consume, politicize, and shape the public narratives of these crimes, often to the detriment of the vulnerable people at the center of these stories.

She spoke with Jezebel about biases in crime reporting, amateur detectives trying to solve murders online, and why you should never make a podcast about her if she goes missing.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JEZEBEL: You write in the book you know you’ve been collecting these stories of women drawn to crime, who can’t claim these crimes for themselves, for ten years. How did the structure of this book, the categories of the detective, the victim, the defender, the killer, come to you?

RACHEL MONROE: The idea of writing about crime stories and the draw that they have, and in the way that particularly women feel compelled by them, that was something I’d been interested in for a long time. I was also feeling really unsatisfied with a lot of the answers that I saw out there. There’s been a lot of really smart writing about true crime but I felt like in the same way women’s appetites are both literally and metaphorically policed, it felt similarly with this realm of interest. People would either be like this is good or this is bad. This is permissible, this is not permissible.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-