Revisiting Nickellennium, The Millennial Time Capsule of a Brighter World That Never Came

In DepthIn Depth

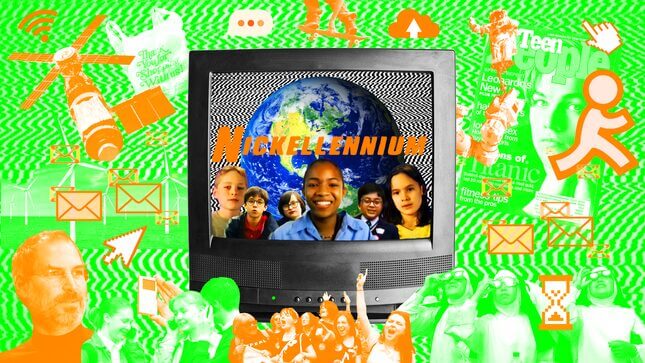

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, Shutterstock, Screenshots via YouTube)

Brendez Wineglass, a 12-year-old Black girl wearing dainty earrings and a broad grin, had a very simple plan for a more just and common-sense future, mirroring that of many children living under the tyranny of sensible bedtimes, mandatory vegetable consumption, and the kid’s table at Thanksgiving. Wineglass was matter-of-fact in her conclusion: “We could probably have two different cities. There’d be a kid city and an adult city.”

While Brendez dreamed of a land where kids ruled, Maddy longed for a machine that would make her brother shrink, Nishant dreamed of being a kid forever, Ishma hoped people would be less racist, Alicia fantasized about the end of bland uniformity, and Tiffany just wanted to take care of her mom. Their stories were all part of Nickelodeon’s Nickellennium, a 24-hour, commercial-free documentary that aired on January 1, 2000, featuring over 600 children from around the world speaking candidly about their hopes and fears for the future and the realities of the present.

“God didn’t create us to be rich and stuff, God created us to be happy, so I think we should all be naked and stuff,” River said; “I don’t like being naked, I think being naked is nasty,” Sheraine countered. “I like clothes. Clothes is fashion.” Ultimately, they came to an agreement that people should do what makes them happy.

Like many others, I tuned in on the first day of a new century, age nine, and watched as my peers discussed the issues of the day and dreamed of the future. While the adults were nervous about the implications of Y2K, for us kids, the hype over a new century—a new millennium—and the hopes that came with it were intoxicating. The internet was more accessible than ever, flooding homes with the most exciting technology in decades. The calendar promised a fresh start, a clean slate, a runway for the sort of flying-car future that we saw on Jetsons reruns, and the metallic latex glory of the Disney Channel’s 1999 original movie Zenon: Girl of the 21st Century. The documentary didn’t radically reshape my outlook on the world, but I do remember feeling a sense of camaraderie with these real kids from different countries, with different accents, who spoke different languages, who had hopes and dreams and fears and likes and dislikes just like me.

While the adults were nervous about the implications of Y2K, for us kids, the hype over a new century—a new millennium—and the hopes that came with it were intoxicating.

By the end of the next year, whatever good cheer and optimism there was to be had about a peaceful century shattered. First, the Internet bubble popped, one of many economic upheavals Nickellennium viewers would witness. Then came September 11th and the American response that turned the rest of the world upside down. The events that followed a cheery, hopeful turn-of-the-century included multiple wars, color-coded terrorist threat levels, economic collapse, the rise of right-wing extremism, commonplace mass shootings, increasingly dire climate disasters, continued economic stratification, and, now, a fatal global pandemic that has killed over 1.2 million people worldwide.

It’s been 20 years since Nickellennium aired, but as an artifact of the ’90s-’00s cusp, the documentary has stuck with me as an eerie calling card from the past. Recently, I dug up the five-hour YouTube upload and rewatched all of it, gazing at the faces of these children—my cohorts—who are now adults in their late 20s and 30s, who couldn’t have predicted the calamity that would define their generation, and I wondered how they’d fared in the years since. So I sought out Nickellennium participants to find out what it was like to film the documentary, what they’re doing now, and whether the last two decades have left them thoroughly jaded or still hopeful for a brighter future ahead.

“I am not scared, I am not scared of the future,” said an Indian boy named Siddharth. His face is plump as he smiles in his smart navy blue school uniform. A fast-paced, vaguely hip hop dance beat plays in the background. “I like the future.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-