The Beautiful Fantasy of the Pretty, Crazy Girl

Latest

In August 1953 a young Sylvia Plath left a note informing her mother that she was “Taking a long hike.” Everyone who spent their adolescence reading and rereading The Bell Jar knows what happened next—two days later, she was found in a crawlspace beneath her family’s home with a jug of water and eight sleeping pills remaining out of a bottle that had once contained 48.

When Plath’s mother reported her missing, The Boston Globe ran a brief mention of the disappearance; the headline read “Beautiful Smith Girl Missing at Wellesley.” It’s impossible to know whether or not anyone would have cared about the “missing” without the “beautiful.”

Sylvia Plath’s celebrity has outlived that of so many of her contemporaries. Her husband, Ted Hughes, the more famous of the two while they were married and the root of so much of her misery, has largely become a footnote in the Sylvia Plath story. Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Lowell is mostly known outside academia as being a teacher and mentor to doomed poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, also remembered as being a friend to Plath. When I was getting my various English degrees, in “serious” poetry seminars, we studied Lowell’s “Skunk Hour” and Sexton’s “Ringing the Bells.” We hardly ever addressed Plath and when we did it was mostly to mock her as a poet for teenage girls. Plath’s fame is a double-edged sword, on one hand, she’s one of the most-read poets of the 20th century. On the other, her readers are often dismissed as a certain type of girl: young, lonely, and looking for inclusion in an elite sorority of beautiful, crazy, brilliant girls like Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Wurtzel, and a handful of others whose names call to mind posh, stylish instability.

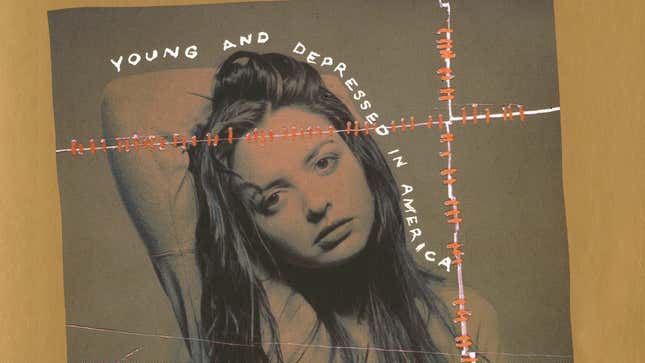

And while I would never mention it in a graduate poetry class, I was one of those lonely teens mooning over Sylvia Plath and Elizabeth Wurtzel, whose memoir Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America made her a late 20th-century successor to Plath’s legacies of both prettiness and craziness. Starting at around age 11—the same age that Wurtzel says she first began cutting her legs to the Velvet Underground in Prozac Nation—I memorized “Mad Girl’s Love Song” and “Daddy” while Fiona Apple’s Tidal played in the background. By the time I got to Wurtzel, I had a pretty good sense of the kind of girl I wanted to be: beautiful as I was crazy.

Prozac Nation, published in 1994, built on what Sylvia Plath had started decades before. Wurtzel was candid about the desperation and self-absorption of chronic depression in a way that the New York Times labeled the as the same “irritating emotional exhibitionism of Sylvia Plath’s Bell Jar.” But it wasn’t irritating to the girls who loved The Bell Jar’s protagonist, Esther Greenwood—a thinly veiled stand-in for Plath herself—like an older sister. Those raw confessions didn’t so much put me in a position of empathizing with young, angry, and desperately sad protagonists as they inspired a feeling that the protagonists were empathizing with me.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-