Image: Angelica Alzona/GMG

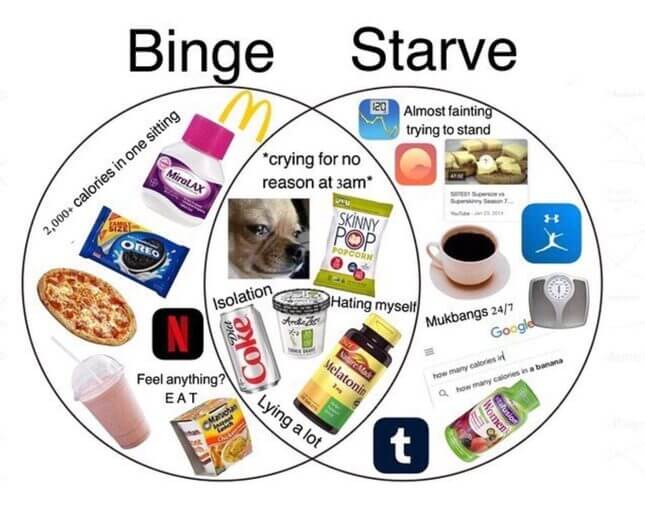

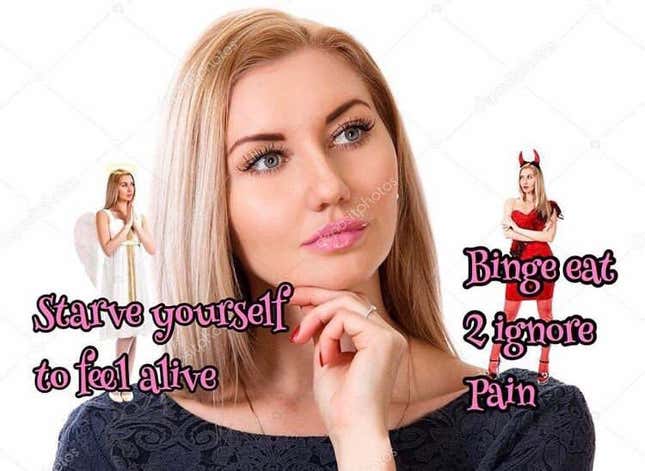

Online eating disorder subculture, pockets of the internet where largely young women and girls share inspiration and information on ED behaviors, has always been a black hole of calorie counting and exercising. Little has fundamentally changed since the days of pro-anorexia Livejournal communities, forums, and blogs of the aughts. There’s still thinspo (short for thinspiration; photos or videos of thin people) and shared tips on fasting, low-calorie foods, and working out. But if the Tumblr era of the early 2010s was defined by black and white GIFs of soft-grunge girls with thigh gaps, then the current Twitter era is defined by self-deprecating memes that add an element of dark humor with a dash of empowerment rhetoric to behaviors like fasting and purging.

ED Twitter is composed largely of teen girls and young adult women who are open with one another about their strained relationship with food. There are people with “ED vent” accounts who say they don’t promote eating disorders but simply want a space to gripe about their eating disorders without judgment. Many accounts explicitly note in their bios or pinned tweets that they’re not pro-ana (pro-anorexia) or other eating disorders. One Twitter user described the difference as such: “ED Twitter: vents about struggles they can’t talk about irl, offers support and shares content so people don’t feel alone; pro-ana Twitter: tweets pictures of Cassie from Skins with the caption ‘I haven’t eaten in three days so I could be lovely,’” referencing the British television show’s character Cassie Ainsworth, whose fictional anorexia has been glamorized for over a decade in eating disorder circles. The Twitter user then urged people to “PLEASE KNOW THE DIFFERENCE.”

Pro-ana sentiment is no longer acceptable among the young women and girls who currently contribute to ED Twitter. They have come of age during an era in which a certain woke savviness about mental illness and body positivity are part of the lingua franca. And at a time when anything and everything can be rebranded as empowerment, ED Twitter—and the specific brand of ironic internet humor that keeps it afloat—feels very much like the same enabling communities that came before. It’s just been repackaged with a “lmao.” That mix of empowerment and irony is only a surface posturing. Dig deeper and the lines between older forms of online ED communities and their current iteration seems to blur.

Jessica Betts, a registered dietician and eating disorder specialist, told Jezebel that while having a sense of humor about an eating disorder can be healthy, laughs should remain in the arena of recovery. “ED Twitter can also be triggering because well-intended posts can be interpreted in so many different ways. I’d argue so much of the need to not feel alone in struggles actually keeps these individuals stuck,” Betts said.

Like their predecessors, many participants in ED Twitter have usernames that include words like “skinny,” “bones,” “thin,” “cal” (short for calories), “craving,” “zero,” “starve,” etc. It’s common for people to list their current weight (cw) and goal weight (gw, or ugw for “ultimate goal weight”) in their bios. Some do “body checks” in the form of selfies that act in the same way that anybody’s selfie does: validation, but from their fellow ED sufferers who experiment with extreme calorie restriction diets or fasts.

Screenshots from fasting apps like Zero are common, as are tweets about Halo Top, a low-calorie, high-protein ice cream with aesthetically pleasing packaging that, to these communities, feels “safe” to eat. (Neither Zero nor Halo Top responded to requests for comment on their popularity among girls and young women with eating disorders.)

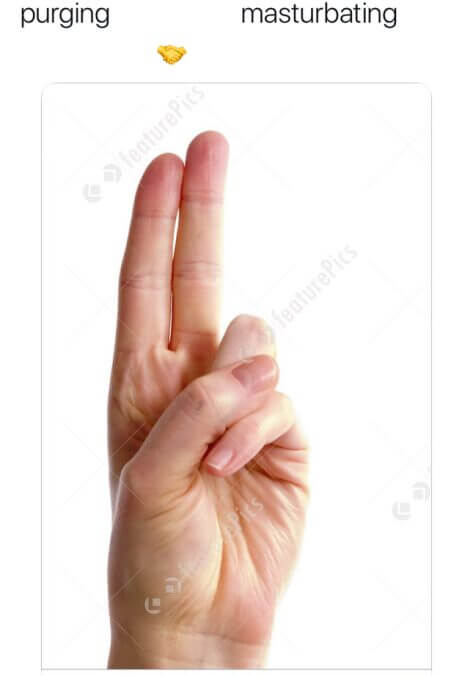

Some list the number of days since they’ve binged in their Twitter names, both as a point of pride and of self-flagellation. There are posts about calorie counts, binging and purging, parents that don’t understand and IRL friends who are convinced of their recovery. There are wistful tweets about the model Kaia Gerber or the members of K-Pop groups like Blackpink and Red Velvet. To call these memes thinspiration may be a step too far, and semantics are deeply important here. They plead for soothing words from their followers in the wake of a binge. Followers usually oblige, reminding each other of the illusions of water weight and the importance of self-care. It’s not unusual to see a frantic tweet from someone in ED Twitter asking their followers if they should eat or skip a meal (followers will often encourage them to eat).

It’s popular to use a voice that blurs the lines between sincerity and internet irony. This isn’t special to ED Twitter, but in this corner of the internet, it feels uniquely dire. Depression memes about sleeping all day feel tame compared to memes about purging, thigh gap, and green tea fasts. Deciphering from hyperbole and sincerity becomes a fool’s errand.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-