The Five Proves Jack the Ripper's London Is Too Close for Comfort

In Depth

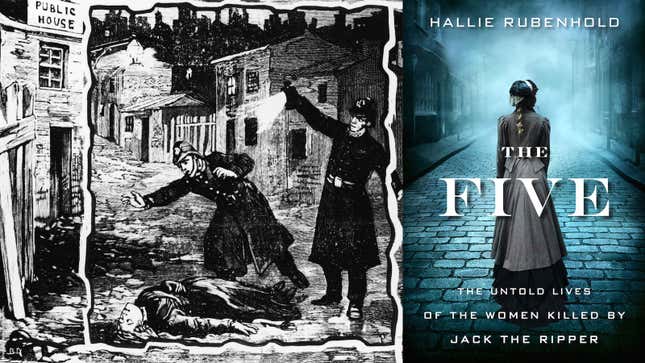

Anybody who knows anything about Jack the Ripper knows this: He killed “streetwalkers” working the roughest area of Victorian London. With her new book, The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, Hallie Rubenhold complicates that narrative—and wrenches the story away from a serial killer who’s been elevated to the point of fascinated worship.

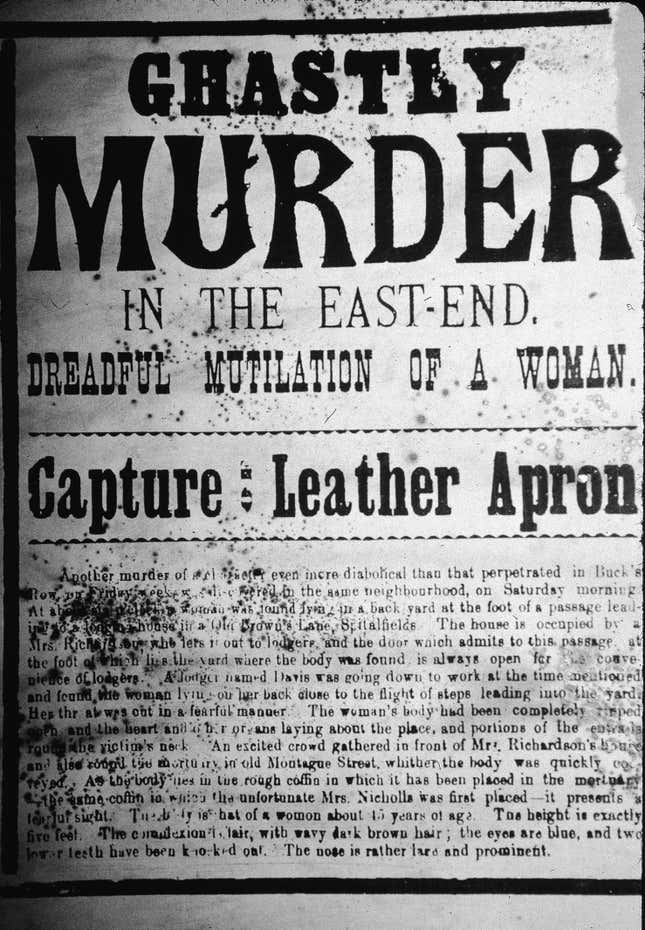

Rubenhold’s project is very simple, and yet unbelievably rare in the thoroughly picked-over territory of “Ripperology.” For over a hundred years, people have been obsessed with finding and naming the “real” Jack the Ripper. Every few years, somebody comes along with a new theory or new approach that promises to solve the mystery. These approaches are invariably forensic, obsessed with the details of the Ripper’s movements and techniques. These dead women are nothing but evidence and pretext. From day one, their presumed profession has been taken as permission to turn the whole thing into a lurid, sexualized spectacle. The deaths of Elisabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes on the same night, September 30, 1888, is often referred to as “the double event,” as though it were two movies for the price of one.

In contrast, The Five explicitly avoids the murderer, the question of his identity, and what exactly he did to each woman when he murdered her. Rubenhold traces the life of each woman up until the night she died; sometimes she discusses the aftermath, but she refuses to rehash the crime scenes themselves and draws a curtain over their deaths.

Instead, we learn that Polly Nichols was born to a Fleet Street blacksmith and lived for a time in a Peabody building, a charitable attempt to provide affordable, high-quality housing for the Victorian working-class open only to the “respectable” poor and maintaining strict criteria for residents. Then her marriage fell apart—her drinking problem likely contributed—and started her on a downward spiral that eventually landed her in Whitechapel, essentially homeless. Annie Chapman followed a similar path. She was initially married to a coachman with a prestigious place, putting her in the upper ranks of the working class—until her drinking, too, became so completely out of control her husband’s boss demanded he cut her loose. She was on and off the streets, despite the efforts of her comparatively prosperous, teetotaler sisters.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-