The Larger than Life Legend of the Regal Blueswoman

People who say Bessie Smith would have said, “I went to see the Empress,” and everybody would have known who they were talking about.

BooksEntertainment

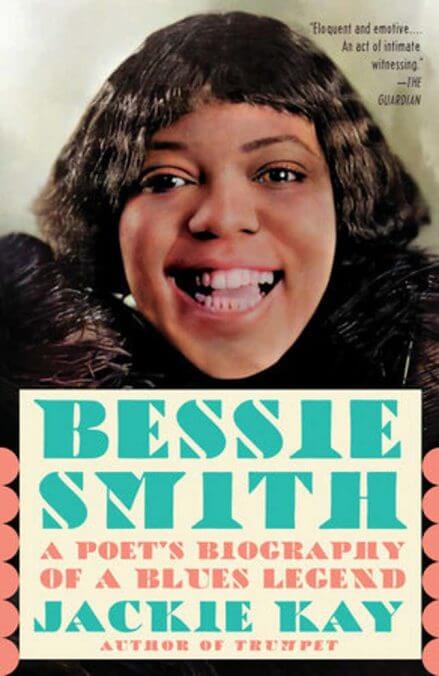

Image: AP Photos

The fact that we ever got to hear any of the classic blues singers at all is a total historical accident. Mamie Smith was the first to record a blues song, “Crazy Blues.” The Okeh Record Company were trying to find Sophie Tucker to record some songs. Her voice was mellow and she was white, but they couldn’t contact her, so they decided to take a risk with Mamie Smith, a black vaudeville singer who didn’t have half of Bessie’s on-the-road followers. The first record Mamie Smith made with the Okeh label was not a blues. But for the second, her gutsy manager, Perry Bradford, persuaded the Okeh company to let her sing the blues backed by a black band. The result was “Crazy Blues,” which was cut on August 10, 1920. It was a huge hit, selling over a hundred thousand copies during the first month of its release. Little business sat up and wanted to be big business.

The blueswomen had taken the blues from backrooms in backstreets first onto the stage, and now onto the record.

The blues were changed by the blueswomen, no longer a folk music sung by folk in the fields, calling and responding to one another while they worked, or while the sun set, folk who wore poor country suits that hadn’t been made for them, or vests with holes in them. We have all seen the pictures. In fact, the picture has come back recently in stereotyped romanticization of the old bluesmen. Now they are being used to sell beer in television and cinema ads, sitting on that sepia porch with the bad-fitting brown suits to sell a bottle of beer. These old bluesmen are considered the genuine article while the women are fancy dress. The poorer the bluesman looks on that run-down porch, the more authentic his blues. The image of the blueswomen is the exact opposite of the bluesmen. There they are in all their splendor and finery, their feathers and ostrich plumes and pearls, theatrical smiles, theatrical shawls, dressed up to the nines and singing about the jail house. The blueswomen are never seen wearing white vests or poor dresses, sitting on a porch in some small Southern town. No, they are right out there on that big stage, prima donnas, barrelhousing, shouting, strutting their stuff. They are all theatre. This combination of theatre and truth is at the heart of the blueswomen. They might be dressed up as divas, queens, and empresses, but they are still telling it like it is. The audience never doubts the truth of the humor or the truth of the sadness, as Sally Placksin writes:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-