Jezebel’s July Book Club Pick: ‘The Bombshell’ by Darrow Farr

Farr's "delulu" protagonist plays a Patty Hearst-like role in this novel about being 18 and becoming the face of a militant independence movement.

Photo: iStockphoto BooksEntertainment

If you’re reading this from the Northern Hemisphere, congratulations, we made it; it’s finally summer. Yes, the heat is oppressive and this will almost certainly be “the hottest summer on record” (again), but it’s the mindset of summer I love the most: The days are longer, the pools are open, everyone is slightly more down to clown than usual. And for me, at least, it’s the season of nostalgia. It’s nearly impossible for me to hear the buzz of cicadas and crickets, smell a barbecue, or even just sit sweltering in front of a fan without being filled with nostalgia for my previous summers.

Nostalgia permeates Darrow Farr’s The Bombshell, which is Jezebel’s book club pick for July. It takes place in summer 1993 (a summer I am not old enough to remember) in Corsica (a place I’ve never been), but because nostalgia is more a feeling and less a memory, those are immaterial details. (I recently watched Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and got intensely nostalgic for high school in the 1980s, a decade in which I did not live! Culture is a hell of a drug.) The era-specific details in The Bombshell evoke this feeling; polaroids, camcorders, TV antennae—the distinct lack of cell phones.

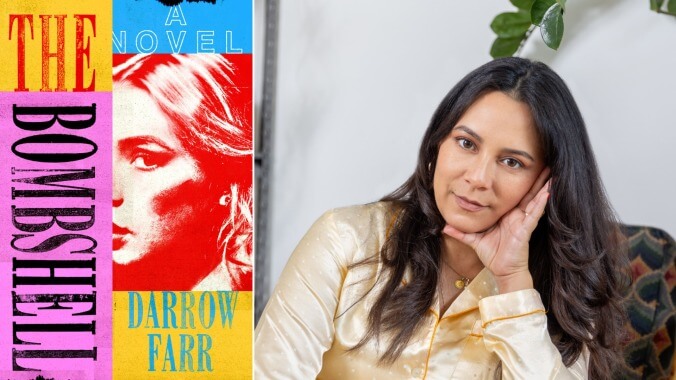

Photo: Pamela Dorman Books; Paul Benson

Farr takes full advantage of her setting, because the plot would be nearly impossible to write in a world with even first-gen iPhones. Séverine Guimard is the daughter of the administrator of Corsica, a French territory in the Mediterranean. She’s been uprooted from her chic life in Paris to spend her last two years of high school in this backwater, and can’t wait to get back to the city of light to begin drama school (though she’d go straight to Los Angeles if her parents would let her; she knows she’ll be a star). She has an obscene dose of self-confidence and considers herself to be extremely sophisticated—especially when it comes to sex—and this combination is borderline insufferable for the first dozen or so pages. (I mean that purely as a compliment to Farr’s ability to recreate the interior monologue of an 18-year-old hottie; in a LitHub essay, she wrote that she wanted to “write a novel about the most extra, delulu teenage girl on the planet, a girl with a literally dangerous amount of confidence.” She succeeded!)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-