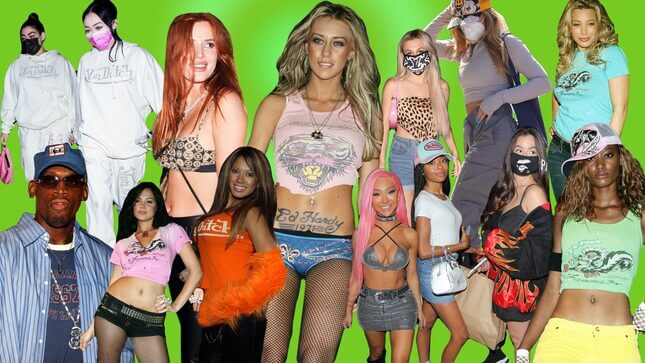

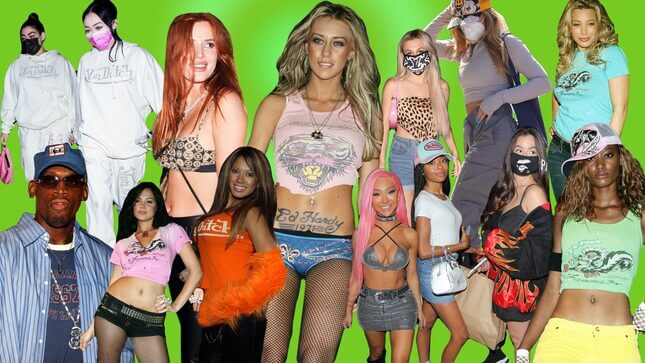

The teenagers have discovered the worst fashion trends of the aughts, and we’re all doomed because of it.

Well, that’s not entirely true, but it is the narrative being pushed by hand-wringing millenials online, whose brief forays into the world of Instagram and TikTok thrift culture have convinced them that low-rise jeans are back to punish us for crimes committed against the midriff in 2004.

Online, but most especially on TikTok, it’s easy to find oneself filled with a creeping sense of dread that young people have almost universally been radicalized into the cult of the worst fashion offerings of the 2000s, solely through a quarantine spent revitalizing their own aesthetics and senses of identity. A scroll through the For You Page, on its worst days, is filled with Von Dutch paraphernalia, butterfly clips, ironic Ed Hardy shirts, and other peculiar Claire’s accessories from nearly 20 years ago. Once dubbed “alt fashion,” more contemporary youth trends now skew towards a return to these trends, seen most prominently on TikTokers like Addison Rae and her cabal of look-alikes, that call back to an era where Holly Madison might mix a Christian Audigier-approved pair of jeans with a bedazzled Playboy Bunny crop top and chunky wedge sandals, chunky blonde highlights sparkling in the paparazzi camera flashes.

The event horizon of this resurgence could, more recently, been seen in a TikTok video that sent internet-using adults into a tailspin this week, when one TikToker posted a video from “ThriftCon” in Atlanta. In it, youths can be seen lusting over ironic Nickolodeon merchandise, sky tops, hideously bedazzled jeans, and all other clothing items that haunt one’s Facebook photos if one scrolls back too far.

The video, and these trends’ resurgence amongst young people, have been generally misunderstood by onlookers. Many fashion critics rightfully accuse the youth of lacking a proper understanding of fashion history, but this is hypothetically true for any generation, not just the ones burgeoning up out of high school and into young adulthood. Others see the proponents of “alt fashion” as having no taste, but such a concept is subjective and permeable. Our parents thought the same of us, and theirs the same of them.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-