How These Filmmakers Got a Motorcycle Group Riding for Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women to Trust Them

"We have a role to play here to end violence in Indian country and across our country," Prairie Rose Seminole told Jezebel of her and Katrina Sorrentino's short film, We Ride for Her.

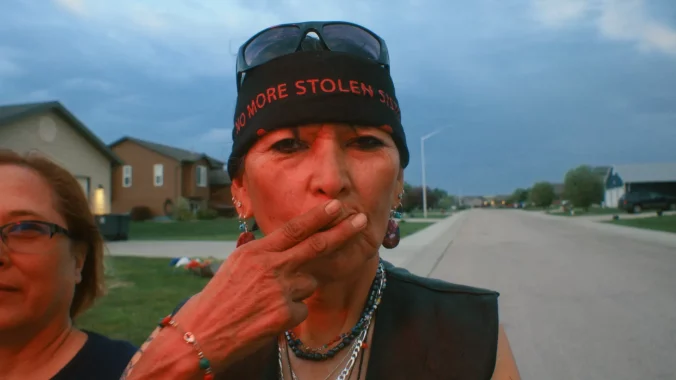

Photos: Katrina Lillian Sorrentino and Cassandra Giraldo EntertainmentMovies

Every year, over half a million people gather in Sturgis, South Dakota for a ten-day motorcycle rally—the largest in the United States. There, among the masses of confederate flag-wielding white men, is an Indigenous motorcycle group of women and femmes called the Medicine Wheel Riders, who’ve been traveling the 1,200 miles from Phoenix, Arizona to Sturgis every year since 2018. Their purpose? To bring national awareness to the countless missing and murdered Indigenous women who disappear or are killed at 10 times the national average.

For those riding, like Lorna Cuny, a member of the Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribe from South Dakota and Co-Chair and Co-Founder of the Medicine Wheel Ride, this crisis is personal.

“The medicine wheel ride is medicine for us, for the families that we are able to help,” Cuny explains in We Ride For Her, a new short film directed by filmmaker Katrina Sorrentino and advocate, Praire Rose Seminole, who documented the group’s ride in 2022. Cuny, of course, isn’t the only rider with a story to share.

“I remember standing in the middle of a field calling the Rapid City police department asking them to please call me back because I wanted to report my sister Susan missing, but I didn’t get a call back,” Heather Taken Alive recalls in the film’s opening, which premiered at South by Southwest in March. “We didn’t know where to start.”

Since 2018, the Medicine Wheel Riders have offered community to women like Lorna, Heather, and countless others. It’s a space to mourn but also to celebrate the memory of women who are so much more than a nameless, faceless statistic.

Over Zoom, Jezebel spoke with Sorrentino and Seminole about how the film came to be, why gaining their subjects’ trust didn’t come until the cameras stopped rolling, and what role their audience can play in helping to end the crisis. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

JEZEBEL: Tell me about the genesis for the film.

Katrina Sorrentino: We Ride For Her started because Red Sand Project, which is an anti-human trafficking nonprofit, reached out to me. I’ve been working as a documentary filmmaker in the anti-human trafficking space for over a decade now and they wanted to make a doc about one of their community partners who were focused on indigenous rights and indigenous activism at the time. We weren’t trying to make an anti-human trafficking film, so to speak, but we asked them what the most pressing need is in their community right now and they said the missing and murdered indigenous women. Once we knew that was what we’d be focusing on, we started looking for people who could carry a story around it. Then, once we found the riders, we knew we had found our participants. We wanted to take on this topic in a way that didn’t re-traumatize survivors but engender hope in a really dark, dark subject matter.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-