You Can Thank This Forgotten 19th Century Novel For the Christmas Prince Movie Genre

In Depth

Are you racking your brain to figure out where on earth the various Christmas prince movies are set? It turns out they’re basically all the same place: Ruritania.

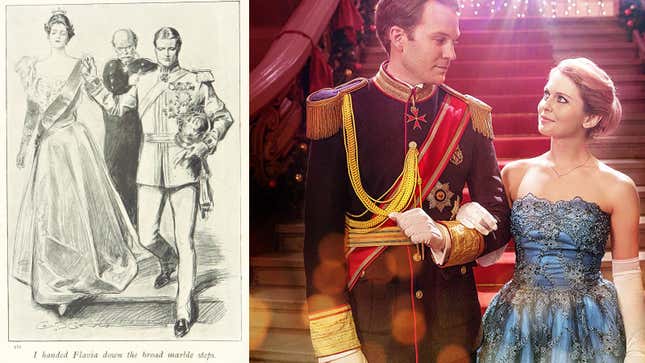

Ruritania isn’t real. It’s the late 19th-century invention of Anthony Hope, author of The Prisoner of Zenda, a swashbuckling adventure story about a man who goes on vacation and finds himself impersonating the king of Ruritania. The book was so popular that it effectively created an entire subgenre of adventure story. Books that followed included Beverley of Graustark, about an American girl who goes abroad to a small European country and bags herself a prince—long before Grace Kelly married into the royal family of Monaco. In other words, the various Christmas prince movies and their vague geographical coordinates are part of a long tradition of generically European pocket countries that stretches back more than a century, weaving through Genovia and ultimately culminating in Aldovia.

Fortunately, in January, Nicholas Daly, Professor of Modern English and American Literature at University College Dublin, is publishing a thorough cultural history of Ruritania and was willing to chat about the subgenre, some of the themes—which echo down into the modern versions—and, most importantly, where these made-up little principalities are supposed to be and why. Our conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

JEZEBEL: What is Ruritania?

NICHOLAS DALY: The first real version we get in a novel called The Prisoner of Zenda, which appears in 1894, by Anthony Hope. It’s very much the swashbuckling adventure version of the story. Hero is on holidays in this small, semi-feudal country in Germany—a little statelet, effectively. For reasons too complicated to explain, he bears a very strong resemblance to the king who is about to be crowned. In order to thwart a coup, our hero gets drafted to replace the king, who has been drugged, then kidnapped.

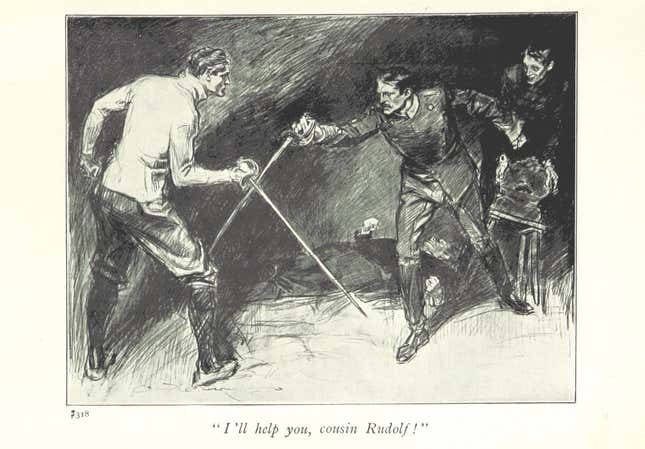

He pretends to be the king for a while, and this works pretty well, except that he falls in love with the Princess Flavia, and he realizes that if this goes on long enough, he won’t be able to give up the throne. He’s become too involved. So he decides, you know, duty first, and he and the king’s supporters lay siege to the castle of Zenda and they rescue the king. This means that our hero, Rudolf Rassendyll, has to give up the throne, obviously, but also he has to give up Princess Flavia. They say their tortured goodbyes, he goes back to England, and she goes off to marry the real king. It’s a love story, it’s an adventure story, but it’s also a novel of renunciation, because they both have to give up love in the end for duty and honor and country.

That’s your basic template. Anthony Hope goes back to that in 1898, with Rupert of Hentzau, which is effectively Return to Zenda. After that, you get many, many, many copycat versions—adventure novels set in all manner of Ruritanian places which are first of all German, and then as time goes by, they drift further east. They become more Balkan. Then you get other variations.

The most significant change to the formula is actually by an American author, George Barr McCutcheon. In 1904, he writes Beverly of Graustark, where we switch from the swashbuckling male hero to one where a female lead—our heroine, Beverly, a plucky American girl—is visiting friends in Graustark, which appears to be somewhere in Eastern Europe. We’re never quite sure where it is. There’s more confused identities. People think that she’s somebody else. She meets a prince in disguise, thinking that he’s somebody else, and eventually, she and the disguised prince fall in love and she becomes Princess Beverly of Graustark, an American princess. You can see that The Princess Diaries has a long, long tradition behind it!

The British and American versions probably mean slightly different things. The British version is a fantasy about chivalry and adventure surviving in the modern world. At a time when Britain itself is this major industrial power and a major imperial power, it’s a fantasy about going back in time, or going to a place where the past is curiously present, and where old-fashioned, manly virtues are still important. Men are men and women aren’t, you know, feminist New Women. They are instead beautiful and swooning types. The American one is slightly different, I think, though it is still very much about this little pocket country as being a playground in which various American virtues can come to the fore.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-