Your Country Needs You! (To Sew)

In Depth

Across the country, sewers are attempting to fill the vast, yawning gaps in our national pandemic preparedness. Some in the fashion industry, including designer Christian Siriano and Brooks Brothers, have turned at least part of their operations over to the effort, producing protective masks for hospitals. But there’s also a flood of hobbyists and crafters who are organizing themselves, digging into their fabric stashes and whipping together masks for their local hospitals and other essential workers. Online fabric shops are sharing instructions and precut kits sold at a discount or donated; Facebook groups are organizing community-wide efforts.

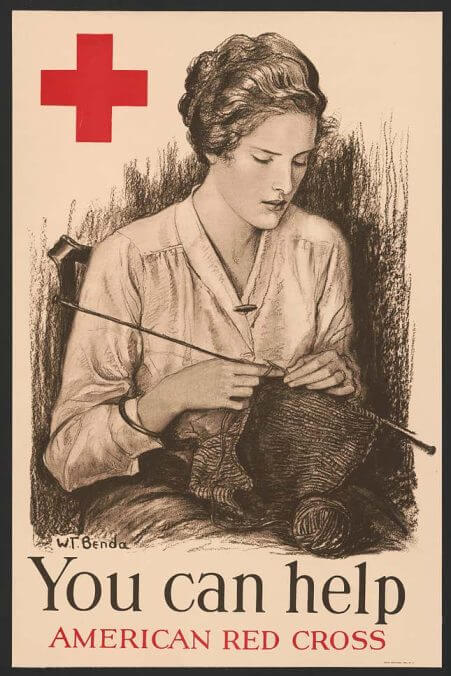

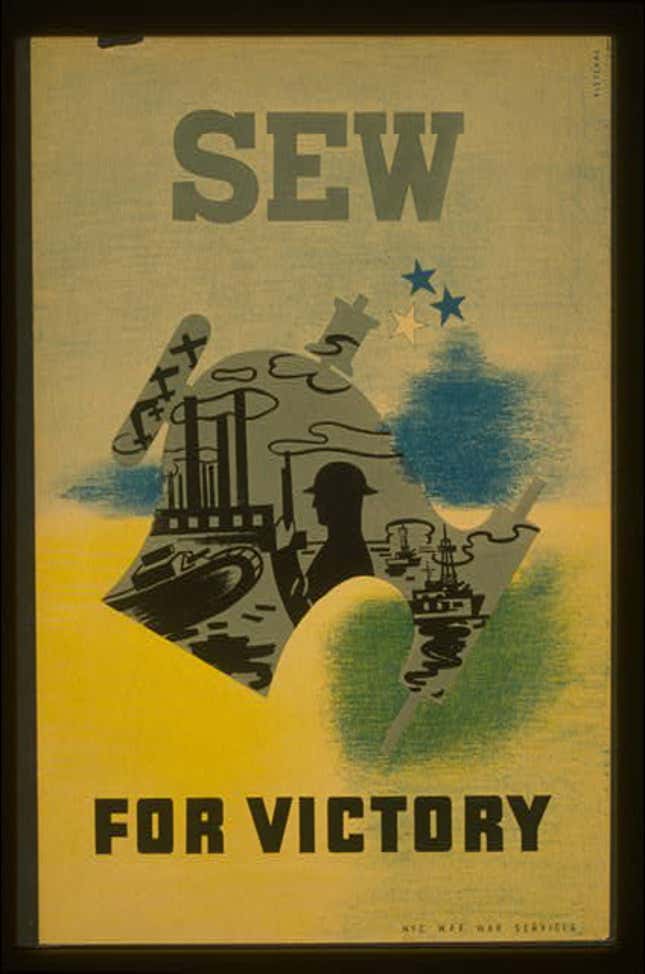

It’s a poignant image. On the one hand, it’s an inspiring story of a group, largely women, rising to meet a vital need, recalling the triumphant wartime imagery of Rosie the Riveter that’s had such a long afterlife in popular feminism.

It stands in a long tradition of sewing circles and knitting efforts as war work for women, who’ve produced everything from flags to bandages to parachutes. But it’s also a grim reminder of how people on the front lines are lacking in the most basic supplies. Essential workers, including nurses, doctors, home health aides, delivery workers, and the grocery store cashiers who are keeping America fed—again, many of whom are women—are being criminally under-supported in this national emergency. That reality makes the homemade masks look more tragic than triumphant.

That reality makes the homemade masks look more tragic than triumphant.

The shortfall has been clear for weeks: Despite the fact that public health authorities have been warning about the importance of pandemic preparedness for years, there just aren’t enough masks. There aren’t enough N95 masks, which are higher grade and more specialized equipment, but there aren’t enough basic surgical masks, either. The national stockpile is running low—and some of those supplies were unusable in the first place—and the crisis has disrupted supply chains. Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested that, in a dire situation, medical workers could even turn to bandanas in hopes of providing some protection—although nothing will be as good as proper PPE.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-