A Night of White Empathy at a Reading for American Dirt

Latest

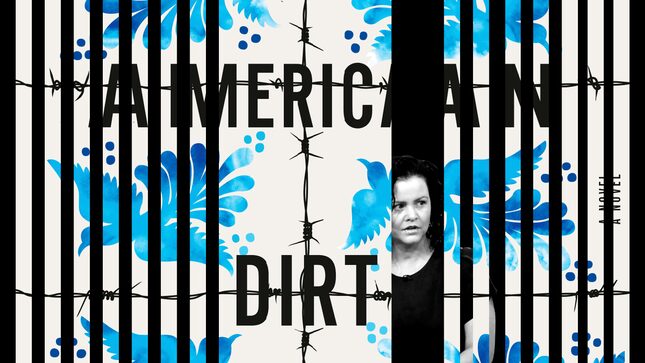

Illustration: Elena Scotti (Photos: Flatiron Books via AP, CBS)

On the top floor of a Barnes and Noble in New York City, on the release day for Jeanine Cummins’s controversial and immediately celebrated novel American Dirt, an audience hums with excitement as it waits for Cummins to take the stage. Rows of middle-aged white women, in between discussing emails from the schools their kids go to, take selfies with their copies of American Dirt, the purchase of which garnered entry to the event. A woman sitting next to me let everyone know that she’s Jeanine’s friend, and I count the people of color in the room besides myself. There appear to be eight, not including Barnes and Noble employees. When someone close by says, “There’s Jeanine,” the room stops, and everyone turns to the back to look for her.

American Dirt is a novel following a fictional mother-son duo as they flee narcos in Mexico into the supposed safe haven that is the United States. The book, which purports to tackle the lack of sympathy towards migrants worldwide, was sold for a seven-figure advance, and Hollywood has already optioned its rights for a movie. Though it hasn’t been out for a full week, it has already been wildly lucrative for Cummins; the day of her reading, it was chosen as an Oprah Book Club pick, and that morning, Cummins appeared on CBS This Morning, alongside Winfrey herself, to promote its release.

Cummins is smiling and almost tearful as she steps up to the microphone for her reading. She asks the audience to indulge her in her “Oscars moment,” before issuing a roster of shout-outs and thank-yous to the people that helped her on her book-writing “journey”—the people at her publishing company, her family, her real-life friends, her author friends. She thanks the local book club that came to the event. It didn’t occur to me until the end of the hour-long event that there was one group Jeanine failed to thank for making her book possible: Mexican immigrants.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-