Before Serums, Women Had Radium

Made with “ACTUAL RADIUM not ‘Radio-Active Water’”!

BooksEntertainment

Image: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

The discovery of radium, in 1898, by scientists Marie Skłodowska Curie and Pierre Curie quickly captured public imagination on a large scale basis. Newspapers in both Western Europe and the United States reported widely on this mysterious new element and its strange properties. It seemed that radium could do anything, that it could solve all of the problems facing humanity at the time. It showed potential as a super medicine, a modern-day panacea, a hope that could cure the most feared diseases of all—cancer and tuberculosis—and found widespread usage in medical treatments.

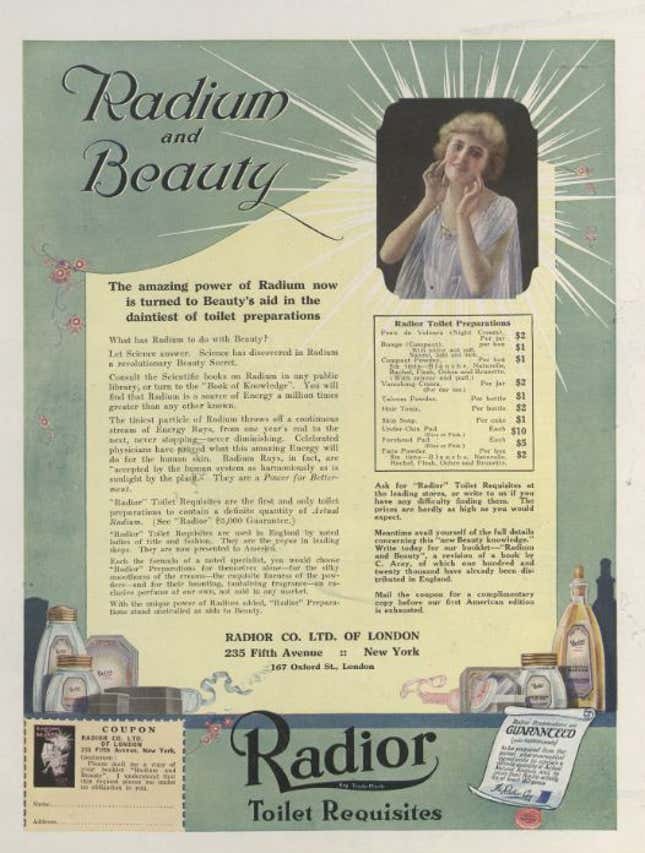

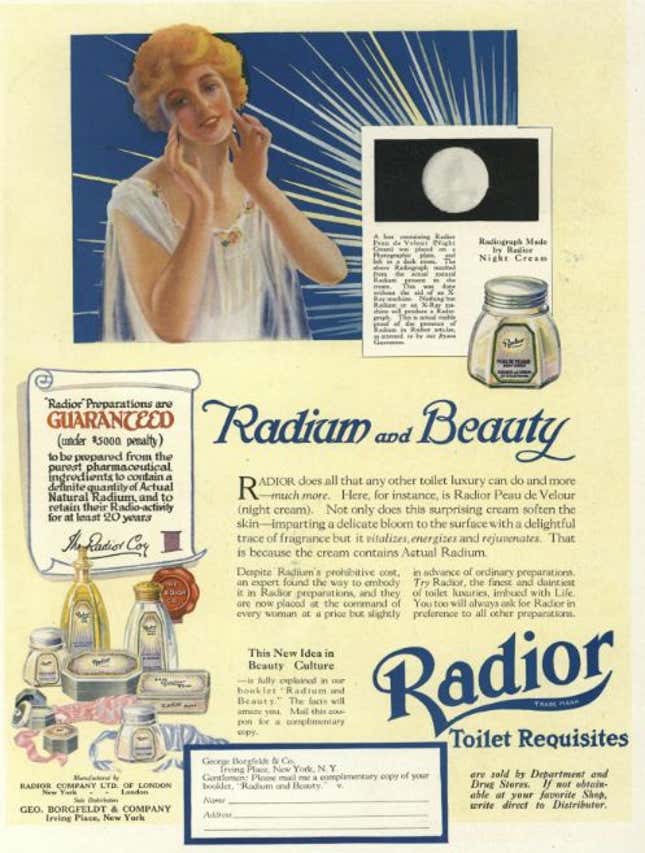

This public interest, alongside the eventual lowering of costs and the expanding availability of radium, presented manufacturers with a retail opportunity that was taken up with enthusiasm in the 1920s and 1930s. The general public was given a chance to purchase a small part of this wondrous substance in products that claimed to harness the healing and energizing powers of radium. The claims of the manufacturers of these products, which ranged from patent medicines to novelty items such as “radium spectacles,” exploited the murkiness of knowledge and understanding of the element, but all shared the similar promise of miraculous results.

Radium was also hailed as the savior to a particular set of problems facing women, including wrinkles, poor skin, excess hair, and crows-feet. A newly emerging mass-market industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the beauty industry was a serious business that advocated a number of innovative new techniques. For other companies wishing to make a case for their modernity and links with science, radium was an obvious choice for research and development purposes. After all, it was a product of modern science created in a Nobel Prize-winning laboratory.

In the 1920s and 30s the streets of Mayfair were crowded with beauty salons, most of which seem to have offered some kind of radium treatment. Some, like those of Helen Cavendish, had developed from small private rooms to larger salon premises due to the popularity of their products and services. Other names, like Phyllis Earle and Feminix were new ventures: opened to cater to the desires of the modern, beauty hungry, woman. The design of the hairdressing and beauty salon had once been modeled on the private cubicles of department stores. However, by the interwar period, they became almost universally (if space permitted) a space divided into two. The first of these was a reception area, which resembled an upper middle-class parlor, and the second, the workspace where the treatments were carried out. The hairdressing and beauty salon had developed as a new urban pleasure—a space where women could be public but private. Even “parlor” and “salon” are terms explicitly invoking the female spaces within a private residence, implying a solid sense of respectability.

The design of the salon spaces was critical—they stressed a sense of luxury and warmth in contrast to the drab life of the majority. But they also designed their premises to appeal to the values of modernism, stressing hygiene, streamlining and cleanliness. These spaces were the height of what it meant to be a modern woman in the interwar years.

An up-to-date salon (and every salon would have strived to be up to date!) would have been a warm and luxurious place. A good salon would have all the mod cons including electric lighting, marble-topped sinks, plenty of hot and cold running water and reclining chairs. The beauty technology on offer included electric curling irons, banks of gas or electric hairdryers, vibrator machines and electric hairbrushes.

The two Phyllis Earle salons (both of which were in London: one at 15 North Audley Street and the other at 32 Dover Street) were the height of sophistication and were designed with the comfort of their clients in mind. “It must be mentioned that in each salon there is a telephone; this is sure to appeal to the busy woman,” noted one editorial.

There was also the Phyllis Earle Institut de Beauté, an onsite training school, which unleashed its trained representatives into the provinces. There they proved very popular, demonstrating products and giving free consultations to a public eager to try this exclusive salon line.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-