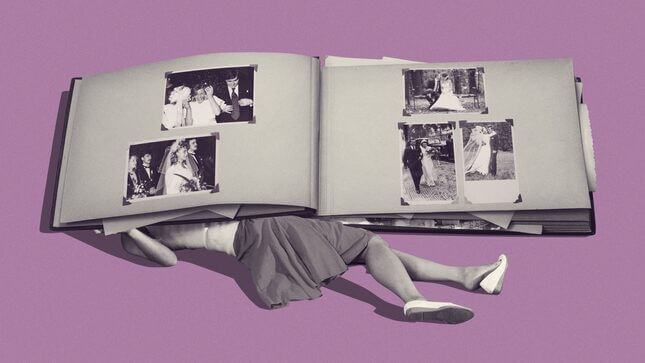

Brides Are Suffocating Under the Weight of Tradition

A feeling of trauma is overwhelming some modern brides, even as they try to rebel against the cookie-cutter wedding spectacle.

In DepthIn Depth

Illustration: Rebecca Fassola

A good bride is prepared for disaster. The wedding is supposed to be the happiest of days, but it won’t go perfectly, so a good bride keeps a doomsday grab bag close by. Self-tanner drops to remedy a sweat streak down a spray-tanned leg; a bleach pen for when alcoholic auntie swings her glass of merlot; and, sometimes, a pin box stuffed with a cocktail of Klonopin, Xanax, and benzos. For panic attacks, of course.

When Janely Martinez got married in Utah in 2017, their sedative of choice was an edible, because alcohol was out of the question at their Mormon wedding, but also so they could reach the dissociative state required to take on the roles of event planner, family drama mediator, and modelesque fixture of guests’ attention. “I couldn’t even get myself ready. I was having mental breakdown after mental breakdown,” Martinez remembered. “Do I care how the cake cutting knife gets to the venue? No, I don’t!”

Martinez and their spouse did what they could to test the boundaries of their religious community, crafting a day that felt more “them.” Martinez, who came out as nonbinary afterward, fulfilled the bride role and gender-swapped their bridal party to have groomsmen (some of whom were gay, which the Mormon Church once taught was curable). Before they set foot in the temple, Martinez was required to meet with a bishop weekly for six months to certify they were a “good person”—a process that involved being asked in not so many words, “Are you gay?”—but chose not to reveal they’d recently taken their close friend to get an abortion. After years of following the church’s “dumb rules,” the least it could do was provide a pretty venue at no cost.

As heightened activism squares off against tradwifery, brides like Martinez find themselves grappling with wedding traditions coded as non-negotiable rituals—the idea of being “given away,” responsibility shuffled from father to husband, the virginal white dress. Forward-looking brides remain in the minority: According to a 2022 Zola survey, just 15 percent of couples found bridalcore traditions outdated, while a third of couples said they felt pressure about incorporating them. But as this contingent of progressive brides divorce themselves from the choreography—ditching the term “bridesmaids,” refusing to toss a bouquet, keeping their last names—some told Jezebel they have experienced what can be described as “bridal trauma,” or severe anxieties as they join the wedding-planning circus.

Theirs is an entirely valid experience said Laura Anderson, a licensed marriage and family therapist with a focus on trauma. Trauma language is all but baked into the commodified marriage extravaganza: Martha Stewart Weddings details “10 Common Wedding-Stress Triggers,” while an advice column from the Knot offers pointers on how to deal with “planxiety.” But Anderson defines trauma as the “way that our body responds to the thing,” not just as the “thing that happens to us.” Atop the nuisances of guest cancellations, pimple freak-outs, and chipped nails, she believes the stress of appealing to the expectations of family and friends could be overwhelming these brides’ nervous systems.

Looking back, Martinez found getting married to be mentally and emotionally exhausting to a degree no edible could fix. “There’s something about a wedding with all eyes on you where you can’t help but have this initial, huge emotional hangover, because you’ve been under a microscope for like six hours the whole entire day…and six months before that,” Martinez said. Despite their little rebellions, masquerading as a Mormon bride—as someone else entirely, really—depleted them. “Being seen up close…isn’t that fun. For the sake of tradition and for the sake of our families, we put ourselves through it. But did we really want to be so exposed? There isn’t actually an amount of money that can make that feel good.”

The Pitfalls of Bucking Tradition

Flouting wedding tradition is, in some cases, more of a shallow aesthetic than a crucial evolution within one of America’s most conspicuous celebrations. Take the black wedding gown: “If a bride wants an edgy look, yet still be super chic and glamorous, a black dress ticks all those boxes,” a recent Guardian piece gloated, listing Selling Sunset villain Christine Quinn as a gothic bride exemplar. But the brides Jezebel spoke to weren’t attempting to fit into an “edgy” trend. They were deeply invested in challenging sexist, racist, and fussy bridal norms, whether by denouncing religions that make saints out of chauvinists or refusing to inhabit a docile, beta-wife role when they are everything but.

Danielle Isbell, a 28-year-old bride from a conservative Christian upbringing, said she was “diametrically opposed” to her religion’s willful neglect of matriarchal power. Her former clergy members preached the idea that God designed men and women for distinct roles—namely leaders and providers for the former, and homemakers and caregivers for the latter. In hopes of reflecting a relationship founded on constant evolution, Isbell proposed back to her fiancé, got married by a woman pastor involved in anti-racism teachings, nixed nuptial language that referred to a masculine God, and met her husband halfway down the aisle so they could approach the altar as equals.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-