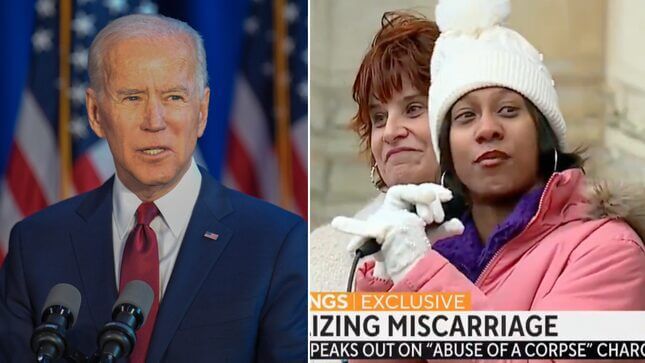

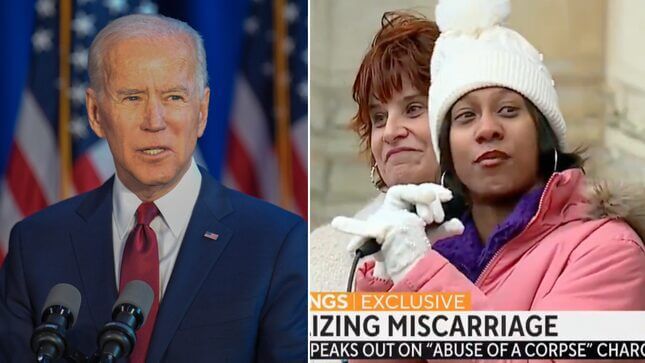

Brittany Watts’ Nurse Reported Her Miscarriage to Cops. Now Congress Wants Biden to Do Something

"Irreparable harm has already been done and we must ensure this never happens to anyone again," a new letter signed by 150+ Congress members states.

Last month, an Ohio jury decided not to charge Brittany Watts with a felony abuse of a corpse charge for having a miscarriage at 22 weeks. Her case has since sparked national outrage over how a hospital regarded a Black woman as criminally suspicious because she asked for an emergency abortion for her nonviable pregnancy, which prosecutors then misused to charge her with a felony for miscarrying.

On Thursday, over 150 members of Congress signed a letter addressed to President Biden and Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, calling on the administration to take actionable steps to stop people from being policed and criminalized for their pregnancy outcomes—and to stop health care workers from reporting pregnant women to the police. This comes after Watts recently shared that her nurse called the police on her, and said Watts “didn’t want the baby” as evidence of supposed wrongdoing.

The letter to Biden begins by pointing to “the longstanding pattern of criminalization of people on the basis of their pregnancies and pregnancy outcomes that has intensified in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.” (Side note: It’s refreshing to see politicians acknowledge that pregnancy-related criminalization has always happened, and abortion bans have only served to shroud all pregnancies in greater suspicion.) “Brittany Watts, like thousands of other people across the country each year, miscarried at her home. When she sought follow-up care at a hospital, the hospital staff reported her to the police,” the letter continues. “Her experience is all too common for Black women, who disproportionately experience adverse pregnancy outcomes due to inadequate health care, and disproportionately experience disrespect, abuse, and punitive responses when they seek pregnancy-related care.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-