The Dark Origins of Gynecology at America’s First Women’s Prison

Incarcerated women uncovered a history of medical experimentation and abuse at their prison, which they detail in Who Would Believe a Prisoner?.

In Depth

Some 150 years ago, a group of Quaker women reformers in Indiana founded the country’s first women’s prison—a solution, they claimed, to protect women prisoners from rape in co-ed prisons. Their stated goals were to “save” those who entered their charge and prepare them to be “useful” members of society, either as housewives or domestic workers. A women’s prison, they said, would serve as a utopia for reform and meaningfully change incarcerated women’s lives.

It’s a narrative that’s transcended that particular era, as women’s prisons are regarded by some as the standard for feminist criminal justice reform. Last summer, Gloria Steinem joined a growing list of activists and politicians who’ve gone so far as to call for the construction of an ostensibly feminist prison—what they defined as a “gender-responsive healing center that is separate from men”—in New York City.

In the last 40 years, women’s state prison populations have grown at twice the rate of men’s. There are currently 29 federal women’s prisons, and about 10% of all incarcerated people are women. The Indiana Women’s Prison stands to this day, a maximum-security facility that boasts of its capacity to imprison over 700 women, as well as “the distinction” of being the first women’s prison. In December, a glowing article described how it provides nurseries and bonding time to incarcerated mothers with newborns—even as they remain confined.

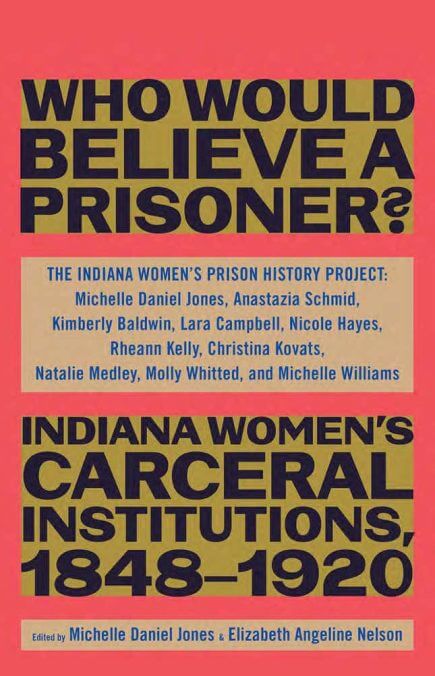

The neat, feel-good fantasy of a women’s prison as a haven for down-on-their-luck women is now being challenged by landmark research conducted by incarcerated women currently or formerly held at the Indiana Women’s Prison, in their new book Who Would Believe a Prisoner?. The book is the product of a nearly 10-year project that began in 2012, when a team within the prison started working on a brochure about its history. Ultimately, they excavated long-buried aspects of the facility’s early days, including rampant sexual violence and medical experimentation that laid the groundwork for modern gynecology.

“The through-line is the use of different kinds of captive bodies to produce new forms of medical knowledge,” co-editor Elizabeth Nelson, who helped launch the college course at the Indiana Women’s Prison that began working on the brochure, told Jezebel. “Our book is a history of the ways the medical establishment has worked with and inside these institutions of confinement.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-