Froth, Feathers, Fluff: The History of the Boa

In Depth

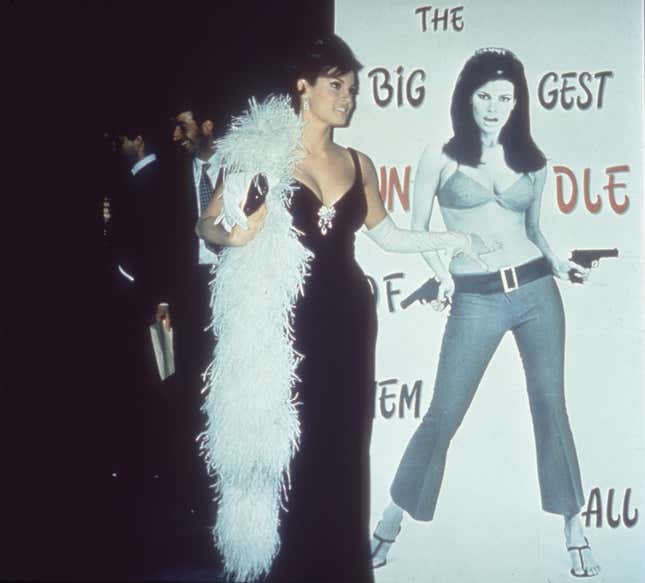

Illustration: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images, AP, HBO)

Like many high school girls living in the early 2000s, I thought there was no higher fashion power in the universe than Carrie Bradshaw. I remember watching an episode from the first season, one of those frantic, self-encapsulated episodes that tells the whole story of a relationship in one 30-minute chunk. Carrie meets a Parisian man with a charming accent and a beautiful Roman nose; they go on a date; he leaves while she is still asleep. She awakes to an envelope full of money on the bedside table: one thousand dollars, cash.

I remember each beat of that episode, including the clothes. I especially remember her outfit for their date—a floral dress, a red coat, and rather horribly, a blue feather boa. A boa! Even I, a suburban teenager who knew little of high fashion, knew feather boas weren’t cool. Wait, were they?

When I first watched the episode, I thought the burlesque-esque accessory was foreshadowing. Perhaps the fancy rich Parisian misunderstood his date with Carrie because she had accessorized with such a gauche piece of neckwear. (Was this the implication of the costume design? I’m still not sure.) I had no idea that feather boas were once considered quite chic. I had no idea what a rich history, one intimately intertwined with Gilded Age riches and 20th-century subversion, Carrie was referencing with her fluffy blue scarf. Like too many viewers, I just saw the sugary fluff, rarely glimpsing the substance that gave the aspirational comedy its shape and structure.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-