Gregg Araki On Why Queerness Has Been a Blessing to His Art

Entertainment

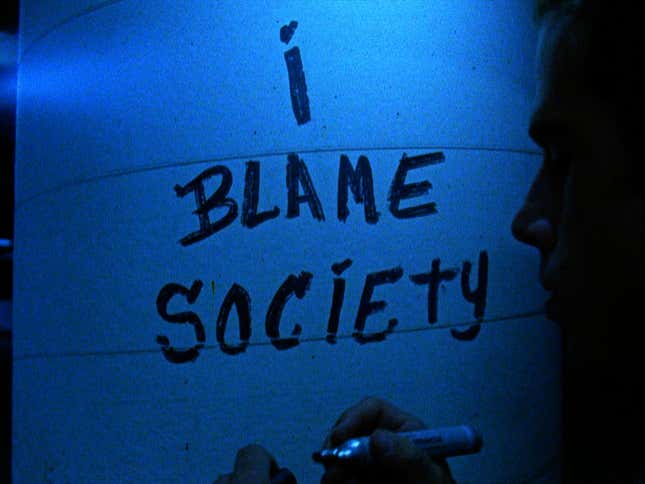

In the past three decades, Gregg Araki has watched his work go from shocking to sweet. The director made his first splash at the 1992 film festival with his third feature, the road movie The Living End. Its heroes, Jon and Luke (a reference not to the New Testament but to Araki’s French New Wave idol Jean-Luc Godard), were HIV positive gay men who reclaimed their country’s refusal to give a fuck about them or their future, spitting it back out in a spray of nihilism and chaos. The movie featured its protagonists engaged in shower sex replete with erotic asphyxiation and close-ups of them kissing (the previous year, much of the controversy surrounding Madonna: Truth or Dare came as a result of a scene in which two of her male dancers made out).

“When The Living End played Sundance, people were horrified and shocked. I heard stories about people getting into fistfights,” Araki told Jezebel via phone earlier this week. “It did really take decades of Will & Grace and Glee and all the other stuff out there to get people to the place of, ‘Yeah, two guys kissing, whatever.’”

The Living End still packs a punch, though largely via its scrappy, DIY aesthetic. Araki shot it on 16 mm, guerilla-style, and was frequently the only crew member on the set. A “gay/lesbian John Hughes movie directed by Godard” called Totally Fucked Up followed in 1994 with much the same unvarnished charm. For Pride month, both movies in addition to Araki’s decidedly more polished aesthetically but no less audacious 2004 film Mysterious Skin (which depicts child sex abuse, grooming, and underage sex work), are streaming on the Criterion Channel. With my recent conversations about film canon in mind, I talked to the 60-year-old filmmaker about Pride, his career, the New Queer Cinema movement with which he was affiliated in the early ’90s, and his legacy. “I’m on Criterion,” he said to me at one point. “What is this world coming to?”

The transcript of our conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

JEZEBEL: Do you have a personal attachment to Pride, not in the general existential sense but as something celebrated specifically every June?

GREGG ARAKI: I’ve always been mixed on Pride. I went to San Francisco Pride once, I think. It’s never been that big of a deal for me. I’ve lived most of my adult life out, my work is queer, but that’s because I’m lucky. I was born in California. I have the coolest parents in the world. For their generation, they’re not normal. They’re so loving and accepting. I never had an issue with coming out. I never even really came out to my parents. I think Pride is really important, and I feel blessed that it wasn’t a big deal to me. But it is great because the big message of Pride is you’re not alone. There’s a whole world out here. There’s a whole world within the world where you’re safe, where you’re loved, and where you’re accepted. I think that’s so important, even today.

I don’t have much use for a month dedicated to Pride because I live my pride every day. I wonder if you see your movies as a similar expression.

Yeah, it’s that “we’re here, we’re queer.” It just is. I think that’s kind of why my movies are never about, “I’m gay, what should I do?” It’s like, “I’m gay and now there’s some dude with a gun.” [Laughs] They take it as a part of life, in a way that it’s a part of my life. It’s a reflection of my own world and my own experience.

As a moviegoer, I’m not really interested in the white, straight, cis, male story anymore.

Via feedback or whatever, did you encounter any hardship from making movies as openly queer as yours were as far back as the late ’80s?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-