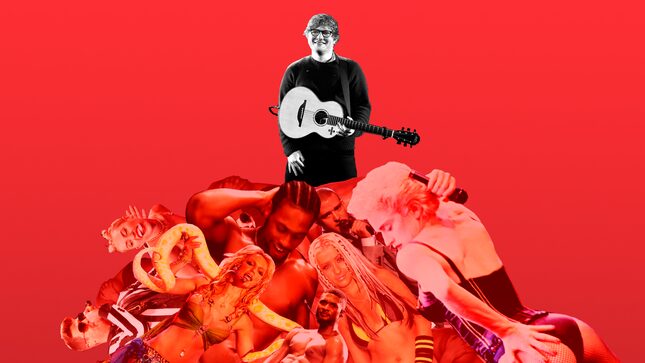

How Pop Music Embraced Death and Lost Its Sex Appeal

Entertainment

Image: Elena Scotti/GMG

After a particularly lackluster 2018 VMAs, so sleep-inducing that the big opening number was the former Vine-turned-pop star Shawn Mendes, New Yorker critic Doreen St. Felix commented that “the first true post-millennial V.M.A.s, was so bereft of shock, sex, and offense that it seemed barely to register.”

In the past MTV’s VMAs, a “music” awards show in sync with what young people actually listen to, has been a lightning rod for provocative pop performance ever since Madonna writhed around on stage singing about sex so good it made her feel like a virgin. It was at the VMAs that Nicki Minaj waxed poetic about good dick, Madonna made out with Britney and Christina, and Miley Cyrus twerked unsettlingly.

The 2018 VMAs reflected a larger change in music, fueled by that Gen Z audience St. Felix referenced. Artists today aren’t pining to be lascivious, slick and shirtless sex symbols like their music forebears. As messages of women’s empowerment have come back in vogue and listeners pine for artists who sing about the darkest, anxious parts of themselves, the writhing, moaning performances that once defined popular music are suddenly archaic.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-