'I Am Women's Rights': How Sojourner Truth Advocated for Black Women

In Depth

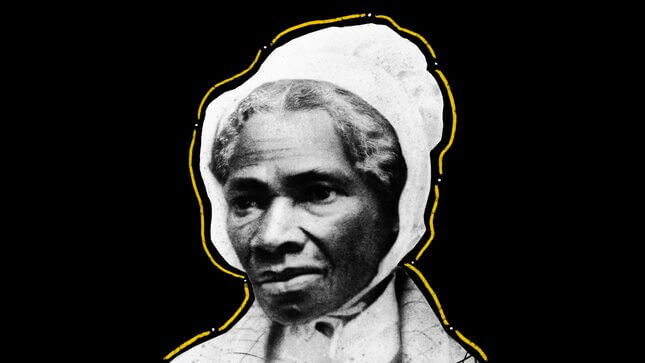

Graphic: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images)

The story of women’s political activism in America and their battle for voting rights has often pivoted around the 19th Amendment. But in her powerful new work of history, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, Professor Martha S. Jones of Johns Hopkins dramatically expands that story and centers Black women in its telling. She draws out the challenges they faced—and the many strategies they developed in the fight, which hold important lessons for our current moment. In this excerpt, Jones looks at the figure of Sojourner Truth, her battle to define herself on her own terms, and the narrowness of vision she had to fight in order to claim her rightful place in the suffrage movement.

Few who met Sojourner Truth forgot the experience. She was an imposing presence, standing six feet tall and speaking with a Dutch accent she had acquired during her early life in Upstate New York. Truth attracted audiences as a former slave and advocate for abolition and women’s equality, and she eventually commanded the podium with unrivaled frankness, humor, and personal testimony. She once told a story, for example, that included a struggle between her desire for freedom and the need to care for her children. She adorned herself in bonnets, shawls, and, later in life, dresses crafted from fine fabrics. Truth knew that audiences had questions about what kind of woman she was, and she became as deliberate as any woman of the 1850s about crafting her own image. Wasn’t she a woman?

Truth’s early life had been unorthodox. Born enslaved, Truth had claimed her own freedom, endured separation from her children, spent years living in a utopian, free love community, and by the 1840s had finally settled in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she embraced antislavery activism. As she embarked on a political career, Truth hoped audiences would understand her point of view—and so she sat for a series of interviews with a white abolitionist, Olive Gilbert, to whom Truth dictated key episodes of her life story. The resulting Narrative of Sojourner Truth, published in 1850, became a peer to the era’s best-known slave narrative, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a Slave. It also became Truth’s calling card, and she sold the pamphlet on the lecture circuit. But self-definition for a woman unable to read and write was not a straightforward task. Gilbert’s desire to show white Americans the wrongs of slavery did not mesh with Truth’s story about a Black woman’s hardships, losses, and the irreconcilable choices she faced when enslaved. The problem of being spoken for and about by others would haunt Truth’s entire public life.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-