Illustration: Angelica Alzona/GMG

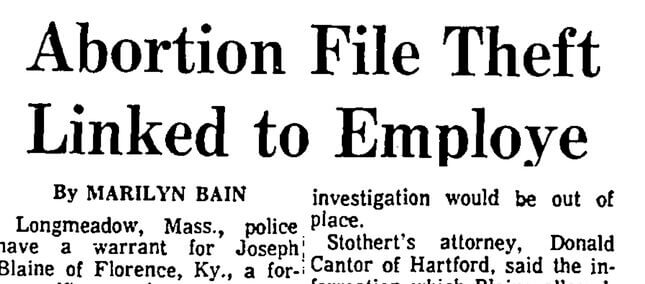

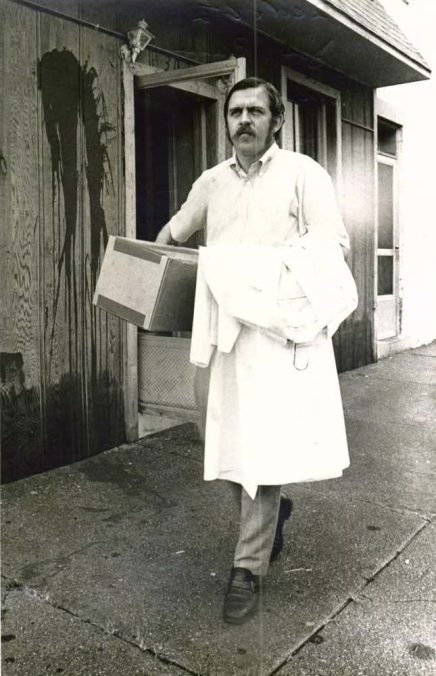

Last summer, I received the first of a string of emails from Joseph Blaine, a man who wanted to share his story with me: despite his lack of medical training, in the decade before Roe v. Wade, he provided illegal abortions. “I am most eager to confess,” Blaine’s first email read, “just how bad it was, with infections, perforations, and deaths of women [and] children.”

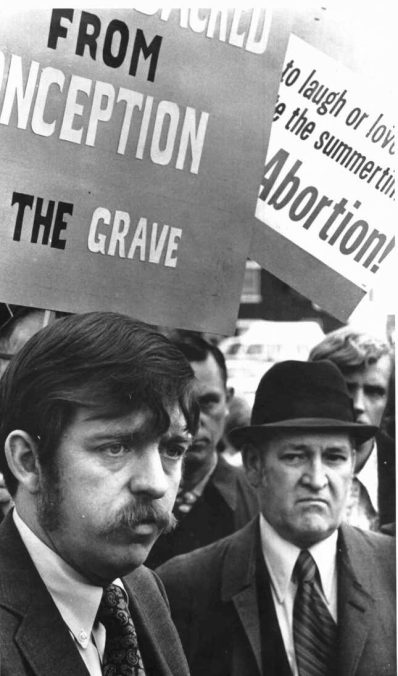

Blaine performed illegal abortions during the 1960s and early 1970s before the Supreme Court legalized abortion. As abortion laws changed, so did Blaine’s business tactics and the language he used to market his services. More than this, Blaine’s career spotlights the varied dangers American women faced before and after legalization.

Blaine did not have any formal medical training. During the 1960s and early 1970s, Blaine was what was commonly known as a “back-alley butcher,” an unskilled and untrained abortion provider that operated on women and, as Blaine told me, injured them. In 1970, Blaine worked for and then operated an abortion referral service, sending women to providers in England and New York state after these jurisdictions legalized abortion. Finally, from Roe until the late-1970s, he operated abortion clinics in the Midwestern United States.

Before the passage of Roe, women with unwanted pregnancies had limited options. They could bear the unwanted child and choose to keep it or give it up for adoption. Women with financial means and connections could try to secure a safe but illegal and usually expensive abortion from a skilled physician. Women with fewer resources, despite the long odds against approval, might choose to ask for a therapeutic hospital abortion. Some women might try to find the funds for a trip abroad where abortion was more accessible. A number of women attempted to self-abort using home remedies or dangerous instruments. In the background, there were always “back alley” providers who had questionable training and motives.

In the 1950s, researchers estimate that anywhere between 200,000 and 1.2 million women sought illegal abortions per year. By the mid-1960s, demographers placed the number at 800,000 annually. A significant percentage of these thousands of women ended up in hospitals for health complications caused by botched and unsanitary abortion. A 1964 article in California Medicine detailed the variety of methods illegal abortionists used:

Intrauterine injections of soap or of peroxide; insertion of coat hangers, knitting needle or welding wire; insertion of air by catheter or by a plaster straw, using a football pump; douches of lysol, soap or potassium permanganate; ingestion of ergotrate, turpentine, magnesium sulfate, castor oil, or of a potassium compound.

A 1970 article hinted at the frightening extent of the medical complications from illegal abortion; it described how Cook County Hospital in Chicago managed over 20,000 illegal abortions between 1961 and 1965 alone. Doctors there treated women for complications stemming from those abortions, including uterine tears and sepsis. Sensational newspaper headlines, meanwhile, regularly alerted Americans to abortion fatalities, but under-reporting and misreporting by hospitals and coroners make it impossible to know the full scale of fatalities caused by illegal abortion.

The already-married 25-year-old Blaine and his 17-year-old girlfriend inhabited this legal and medical landscape in 1965 when she became pregnant. It’s unclear what medical options existed for them in Lexington, Kentucky but Blaine decided to take matters into his own hands. He learned how to perform the operation himself.

“A [veterinarian] taught me,” Blaine said, “using his collie!” He described practicing on the collie as well as livestock. Blaine’s teenage girlfriend became his first human patient, and he successfully caused her to miscarry using an intrauterine device.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-