‘Bitch’ Busts the Stereotype of Female Animals as Docile, Maternal Creatures

From baboon abortions to same-sex avian couples, zoologist Lucy Cooke's book dives into the fascinatingly diverse behaviors of female animals.

BooksEntertainment

When Laura Bush visited Hawaii in 2007, the First Lady approvingly noted that the state’s Laysan albatrosses mate for life. The birds usually return to the same nest with the same partner year after year and have one of the avian world’s lowest “divorce rates.” But, unbeknownst to Bush and everyone else, as Lucy Cooke writes in her new book Bitch: On the Female of the Species, about a third of Laysan albatross couples are same-sex pairings made up of female birds. Researchers, tipped off by the discovery that some nests regularly contained two eggs each year though the birds are only capable of laying one at a time, later discovered that some females mated with males but partnered with each other to raise their young.

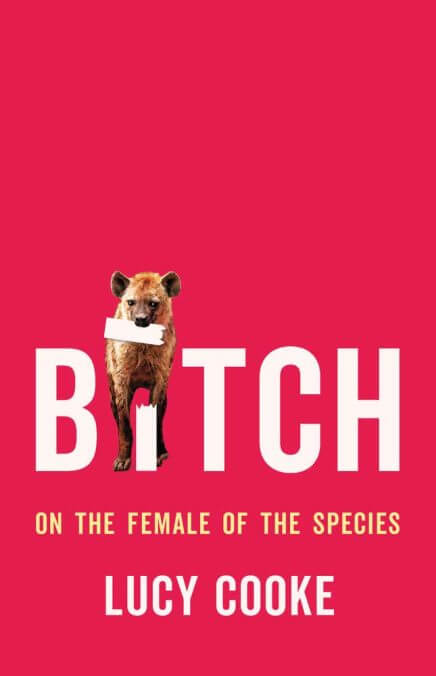

Cooke’s profile of the birds is just one of many in Bitch, which was released in the U.S. on Tuesday and finds the British zoologist on a stereotype-busting, globe-hopping tour of the animal kingdom. The book examines creatures who defy long-held preconceptions of animal world females as submissive, instinctively maternal, and sexually docile—from bonobos to bush crickets.

“If you’re going to define being female, it’s by its varied nature,” Cooke told Jezebel via Zoom. “It’s not about fitting in this particular pigeonhole or these particular stereotypes.”

Cooke, who’s a zoologist and TV broadcaster as well as an author, was taught during her student years that “female animals had very specific roles, and that our roles were defined by our sex, and that we were passive, coy creatures that were second-rate players in the evolutionary story, and that males were the main event,” she said.

It was a belief system that owes a lot to the work of Charles Darwin. Because ova are large, energetically high-priced to create, and in limited supply while sperm are small and ample, Darwinian thinking goes, females are supposedly sexually restrained and males are promiscuous. As the controversial evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, with whom Cooke studied in college, wrote in The Selfish Gene, “The female is exploited, and the fundamental evolutionary basis for the exploitation is the fact that eggs are larger than sperms.” From these asymmetrical gametes all sex-based oppression supposedly follows, as males are free to be roving adventurers while females tend their few, precious offspring.

But thankfully, the story isn’t quite that simple, nor is exploitation that inevitable. In recent years, researchers—many of whom are women themselves—have revealed that the females of the animal kingdom vary widely, and it’s these stories that Cooke highlights in Bitch. “I thought it was about time to tell the truth about female animals,” she said, “and what a kind of extraordinary, diverse, dominant, aggressive, competitive, promiscuous bunch of creatures we are.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-