New Documentary Makes a Shaky and Kinda TERFy Case Against the Birth Control Pill

The Business of Birth Control examines the twisty relationship between big pharma, hormonal birth control, and women's lib.

EntertainmentMovies

As I watched The Business of Birth Control, I remembered my own years-long battle to find an effective birth control method. I tried multiple dosages of The Pill, just doing nothing, and even the arm implant Nexplanon before landing on my non-hormonal copper IUD. It’s fine at preventing pregnancy, which is barely a problem as my primary partner is now a fellow ciswoman. My period still sucks ass. I’m regularly laid up for a day or two each month because of my endometriosis.

I should be this documentary’s ideal viewer. Instead, I walked away from my laptop asking why this documentary was made—there were so many possible storytelling threads to pull, and they were left to hang loose.

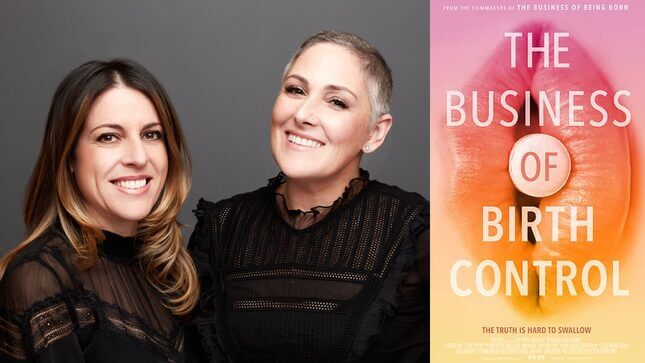

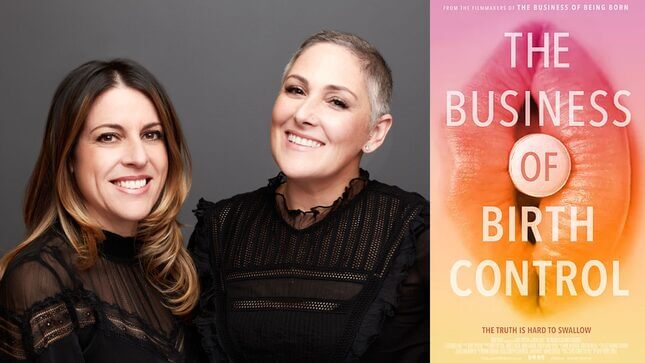

The Business of Birth Control—inspired by Holly Grigg-Spall’s book Sweetening the Pill—is the latest documentary from executive producer/actress Ricki Lake and director Abby Epstein. The team first paired up to create the 2007 film The Business of Being Born and have continued to make films in the women’s health arena. This documentary seeks to untangle the relationship between hormonal birth control, health care industry and feminism. According to the synopsis sent to press: “Weaving together the stories of bereaved parents, body literacy activists and femtech innovators, the film reveals a new generation seeking holistic and ecological alternatives to the pill while redefining the meaning of reproductive justice.”

While I didn’t agree with the supposition that reproductive justice needed to redefined (activist Loretta Ross has done a great job explaining what it is), I was excited to watch this documentary. Finding the right birth control for you does suck, as almost anyone who has been to a well-woman visit can tell you anecdotally. I was so interested to see what kind of data they had found to support my lived experience, which activists would be included, and how they would situate birth control in the larger picture of reproductive health. Instead, The Business of Birth Control felt like it was made by a second-wave feminist who simply didn’t want to advance their way of looking at the world.

Arguably, the most affecting parts of the film are the interviews with grieving parents about their daughters who died as a result of hormonal birth control side effects. Viewers then spend so much time with these parents, who are just beginning a fight against big pharma, with very few victories to show on screen. Their biggest victory seems to be attending a conference about contraception and meeting with a duo of traveling sex educators. The documentary would have been better to lessen the number of talking heads (I lost count) and focus solely on these families mourning their daughters and trying to make sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else. Instead, the narrative is driven by 20-45 second interview clips with doctors, activists, midwives, educators, etc., who are simply less interesting than the people who have experienced significant loss.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-