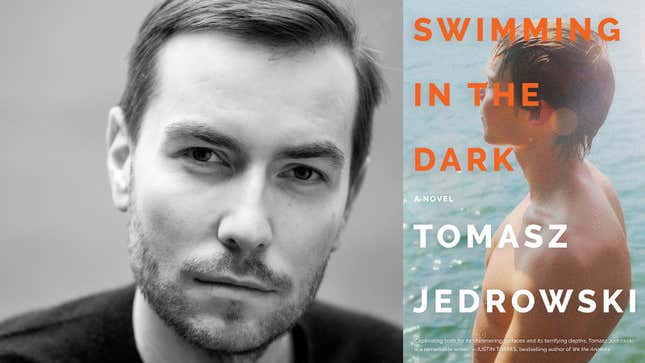

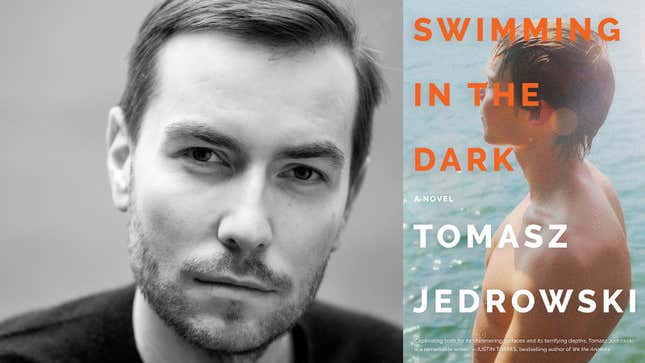

Swimming in the Dark Captures Love and Rebellion Among Men in 1980s Poland

In Depth

It’s hard not to see the context of how we live in now everywhere you look, even back. I watch a movie that features a club scene, and I think, “How can they stand to be so close?” I read about the so-called “plague years” of the AIDS crisis, and my mind instantly draws parallels (and contrasts) with covid-19. It’s especially uncanny, though, to read Tomasz Jedrowski’s fictionalized account of Poland in 1980 in his first novel, Swimming in the Dark. Lines snake outside supermarkets, citizens are ordered to stay at home, the economy collapses. A novel that attempts to capture the turbulent decline of Communism 40 years ago during feels, in many ways, relevant to the here and now.

Besieged Warsaw is both a backdrop to and a complicating factor in the romance on which Jedrowski’s book is centered. It occurs between the radicalized narrator, college student Ludwik, and Janusz, the man he falls in love with at an agricultural camp. Janusz works for the government and has a partial role in which books get published, which is to say that his trade is censorship. So often in modern discourse, when we talk about the roles of assimilationist and radical among gay men, it’s in reference to their relationship with their sexuality, at times reduced to an evaluation of “how gay” they are. (See: The past year and a half of public discussions about Pete Buttigieg.) Swimming in the Dark probes that divide from another perspective entirely and is more compelling for doing so.

It also, at times, half-rhymes with James Baldwin’s virtuosic 1956 novel about love and hate among men, Giovanni’s Room. Certain life experiences of Ludwig’s mirror (or provide alternate takes on) those of Giovanni’s Room’s protagonist, David. But the homage is most blatant in Ludwik’s savoring of the novel (which, because of its gay subject matter, was illegal in Poland at the time) and his passing it on to Janusz. By sharing Baldwin’s resonant meditation on the nature of love among men, Ludwik and Janusz themselves fall in love. “It felt as if the words and the thoughts of the narrator—despite their agony, despite their pain—healed some of my agony and my pain, simply by existing,” says Ludwik, connecting dots from almost 70 years ago to now.

Swimming in the Dark is a lovely, sensitive story in which a sentence whose prose could floor you is always around the corner. (Here is a passage from a reminiscent Ludwik that I particularly loved, which illustrates his great eloquence and inherent shortcomings all at once: “My memory has its limits, of course. It may color in the blanks without admitting to it, dramatize or revise. I guess there is not photographic memory for emotions.”) The manuscript of Swimming in the Dark inspired a six-way auction a few years ago, which resulted in a six-figure deal for Jedrowski. Jedrowski, who was born in Germany to Polish parents, told me about that “surreal” auction last week via video chat from the French countryside, where he is on lockdown. He also discussed his book, sexuality, and Giovanni’s Room. Below is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

JEZEBEL: You speak five languages [Polish, English, French, German, and Spanish] but write in English. Is there anything about English specifically that has inspired your preference?

TOMASZ JEDROWSKI: I’ve never properly thought about it, myself. I feel like English is a tool that hasn’t been imposed on me. It’s not something that I happened to be born into. It’s just something I enjoyed from the very start, and I don’t feel like it’s my parents speaking through me when I’m writing in English, because we never spoke in English. I don’t think it’s society speaking through me, because I didn’t grow up in an English-speaking society. It’s my literary language, because it’s in English that I really started reading books properly. It’s this part of my mind that feels really intimate and private, but not the same as intimacy between me and my family or intimacy between me and my husband. It’s sort of self-intimacy.

Could you talk about the genesis of the book? What prompted you to write about two men in love in 1980 Poland?

For me the genesis of the book is closely linked to me deciding to write at all, when I dared to come out to myself as someone who actually wants to write. I used to be a lawyer and I [went through] therapy, because I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. I found a writing course, and they asked me to write anything. I had decided I was going to be a writer, but I didn’t have an idea. It was more the idea of being a writer that I liked. When I had to write this thing for my writing class, I had this flash in my mind where I could see this guy, who’s a student, fancying this other guy and this sense of not really being able to live that love and also the other guy not feeling exactly the same. It was that image I started with and then I developed it.

Had it been brewing, though? I mean, do you identify as gay?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-