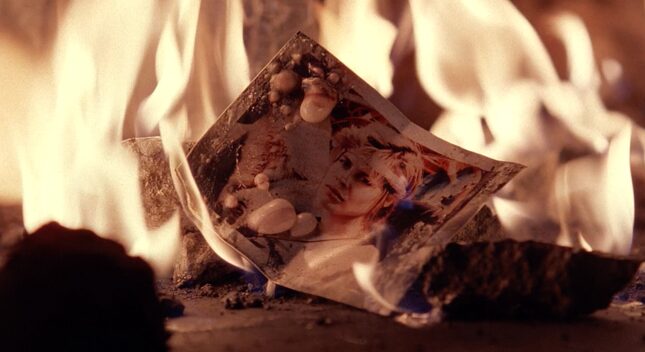

Image: Paramount Pictures

Ever since I had a kid, I can’t stop thinking about Sarah Connor, the heart of the Terminator franchise.

Arnold Schwarzenegger has traditionally been the face of this series, since, after all, he’s the terminator. First, in 1984’s Terminator, he was a relentless killing machine sent from the future by Skynet, the AI devoted to eliminating humanity, to kill the unsuspecting Connor so she couldn’t give birth to the future leader of the human resistance, her son John. Then, in 1991’s Terminator 2: Judgement Day, he played another version of the machine, reprogrammed by future John and sent back in time to protect young John. Arnold is back in the latest installment, Terminator: Dark Fate, but who cares? Because more importantly, actress Linda Hamilton is back, reprising her character Sarah as a hardened, grizzled, gray-haired ass-kicker.

Sarah Connor looms so large in my understanding of the Terminator movies that sometimes I forget the first two installments are absolute cultural classics of the long Reagan era, and that Terminator 2, in particular, is deeply invested in tough-guy heroism and establishing John, the boy whose all-important existence powers the franchise, as a savior figure with budding leadership skills, when he’s not even a teenager yet. (His initials are literally J.C.) At one point in Terminator 2, when John, Sarah, and the T-800 are explaining to the creator of Skynet (aka the AI that will go rogue) why it has to be destroyed, Sarah begins to rake the scientist over the coals for his and his team’s arrogance in thinking they could create artificial life, telling him he doesn’t know anything about creating actual life, feeling it growing inside you. John cuts his mother off, telling her she isn’t being helpful.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-