The Bridges of Madison County: The Most Profitable Midlife Crisis of the ’90s Or Maybe Ever

In DepthIn Depth

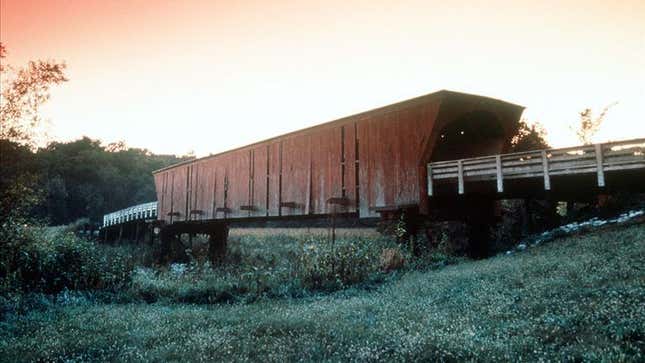

Image: AP Photos

There’s nothing wrong with pitting lust and responsibility against each other; the dynamic is arguably the most compelling engine of sexual tension. I believe wholeheartedly that people over the age of 30—or, god forbid, 40—should be represented as full people with raunchy and shattering desires. There’s nothing inherently corny, necessarily, about a stoic heroine doing the right thing, or a man imagining himself as equal parts cowboy and poet. (In fact, I’m a well-documented fan of exactly that type of guy.) I even have a healthy respect for the power of short affairs to reconstitute a person’s reality in a way that will stick with them for the rest of their lives. But The Bridges of Madison County, the fantastically successful 1992 novel about a small-town mom forever transformed by a short tryst with a stranger, a book pounded out in a masturbatory fever by a professor of business management over the course of 11 days, manages to spoil even the low-hanging fruit and debases every one of these otherwise seductive themes.

Truly, I wanted to lose myself in one of the iconic novels of the 1990s, and there’s never been a better time for a salty person to try a little romance: I’m holed up in a February polar vortex almost a year into a pandemic that’s made it impossible for me to, for example, invite a stranger out for a quick jaunt to a local landmark and fall on his dick in such a way that would define the rest of my life. And, sure, I can imagine being swept away by a hot dirtbag, an artist insofar as his body invites comparisons to sculpture and his truck is full of dented photography gear. I can even, suspending disbelief, place myself in the role of a chaste Iowa farmers’ wife who spends her twilight years pining for a man she absolutely should have run away with, having found her soulmate over the course of four days and three torrid nights. But I cannot, under any circumstances, imagine writing a posthumous letter to my adult children describing how well that dirtbag fucked me as if that were the sum total of what should be known about my inner world. Even in the throes of hypnotic passion, I would never refer, repeatedly, to my lover as a shaman, a leopard, or a bird of prey. At the very least, I would hope that if I were being consumed by longing for a person I just met, I’d push back a bit on his lengthy speeches about how his vanishing breed of wild, valorous man was more biologically suited to throwing spears than putting on a suit.

It has crossed by my mind that I feel this way because I’ve never experienced the kind of love Robert James Waller describes, a love so deep that in the words of its author a person might be taught “what it was like to be a woman in a way that few women, maybe none, ever will.” But then again, Walter, whose tossed-off novel almost instantly manifested an Atlantic Records deal featuring his own songs (about covered bridges, naturally) as well as massively successful Clint Eastwood vehicle—a movie that in turn inspired, among other things, a perfume line and a blank journal featuring Eastwood’s own Bridges-inspired photography–was at one point believed to have based The Bridges of Madison County’s protagonist partially on his wife. And then he left her for the couple’s landscaper, almost 25 years his junior, soon after his acclaimed novel about twin-souled lovers separated by continents made him filthy rich.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-