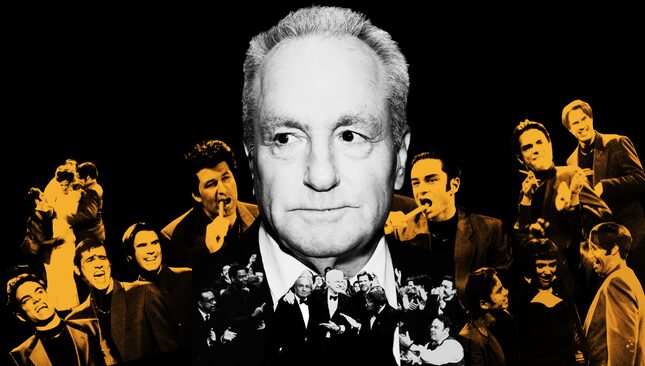

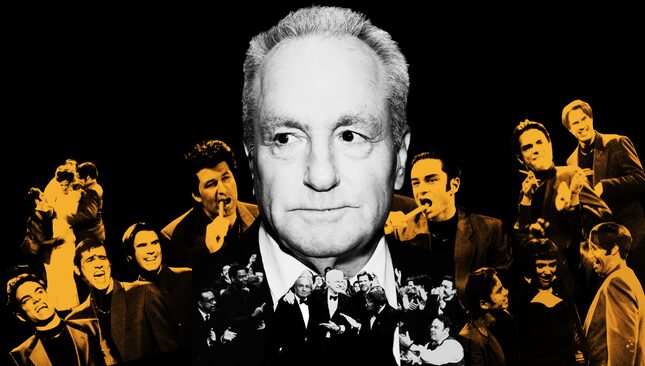

The Divided House of Lorne Michaels

Latest

In Chris Kattan’s new memoir Baby Don’t Hurt Me, he writes that during the production of the film A Night at the Roxbury producer Lorne Michaels called him with an urgent suggestion. Kattan says he had been propositioned by the film’s director Amy Heckerling (“Are we gonna have sex?” she asked him, he writes), which Kattan politely shrugged off. The next day Michaels called him “furious,” saying that Amy apparently didn’t want to direct the movie.

If he wanted to make sure the movie happened, Kattan would have to keep Amy happy, Michaels reportedly said: “Chris, I’m not saying you have to fuck her, but it wouldn’t hurt.” Kattan writes that he and Heckerling eventually did have sex, consensually, but that he was “very afraid of the power she and Lorne wielded over my career.”

Since the book was released in early May, parties involved have rejected Kattan’s story. A representative for Saturday Night Live denied that Michaels encouraged the affair to Page Six, while Heckerling’s daughter Mollie denied the claims the affair was coerced and says that it began after the film started shooting. Heckerling told Vulture that she decided to comment because her mother is a private person who didn’t want to fuel the story by commenting. “I really wish Lorne Michaels would step forward,” she added.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-