The Housewife and the Hustler Is a Necessary Yet Flawed Portrait of Erika Jayne, Tom Girardi, & American Greed

ABC's documentary on Erika Jayne and Tom Girardi's legal battles makes big promises but fails to deliver

EntertainmentTV

The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills star Erika Jayne’s most famous tagline is “I am an enigma wrapped in a riddle and cash.” But from the allegations laid out in ABC’s new documentary on the many lawsuits pending against her and ex-husband Tom Girardi, including claims of legal malpractice and fraud, it seems that at least some of that cash she’s been wrapped up in on television is not actually hers, or her husbands.

In attempting to unwrap the layers of enigma around Los Angeles’s most famous power broker and his star wife, though, it’s obvious that filmmakers at ABC and cultural spectators have become all-too-dazzled by the glitz and glamour surrounding the horrifying malpractice crimes Girardi is alleged to have orchestrated—and that, with court proceedings ongoing, the real story has yet to be told.

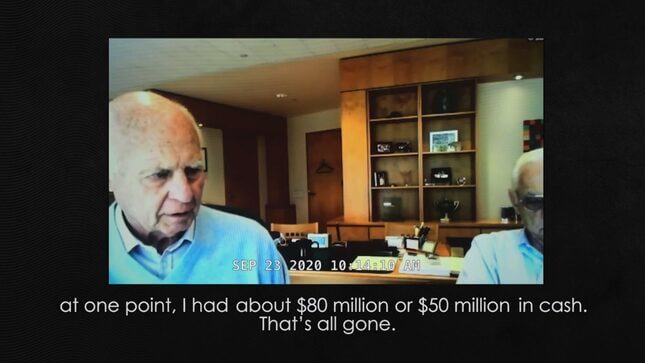

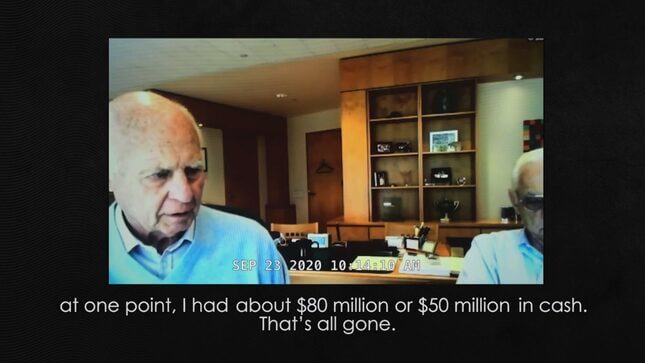

The Housewife and the Hustler, which aired as a special Sunday night on ABC, promised a big payoff, including interviews with Girardi’s alleged victims, most of whom are past clients. In promotional materials, ABC trotted out its access to the insider world of Los Angeles power brokers, having obtained footage of depositions, emails, court transcripts, and firsthand accounts by former employees and peers of Girardi.

It also claimed “insider” sources among the world of The Real Housewives. A more empathetic investigation might first begin with interviews with victims and past clients, those most affected by Girardi’s actions. Instead, The Housewife and the Hustler attempts to lure in gossip vultures, promising big on the secrets its insiders might reveal. How funny that it’s structured like the worst episodes of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, which place entertainment and scandal over empathy or honest storytelling. It takes a third of its runtime to even meet a single past client of Tom Girardi.

Twenty minutes into the special, viewers meet the first of Girardi’s alleged victims who agreed to be interviewed. Joe Ruigomez was a resident of San Bruno in 2010 when a PG&E gas line broke and then exploded—leveling his neighborhood, killing his girlfriend, and leaving him with permanent, full-body burn scars. Kim Archie, a friend of Joe’s mother Kathy, drove to San Francisco to console and help her childhood friend. At the time, Archie said she worked as a legal consultant in Los Angeles. While the Ruigomez family fought to save Joe’s life, they were inundated with requests from potential lawyers, after which Archie connected them to Girardi, a powerful lawyer in Los Angeles. He had, at that point, a proven track record in winning against PG&E, having famously represented the case against the energy giant featured in the movie Erin Brokovich.

Before detailing Joe’s case, and Girardi’s alleged theft of almost all the family’s settlement money, it’s important to note just how powerful Girardi was in Los Angeles law. On this front, The Housewife and the Hustler is wildly successful. Through admissions by lawyers in Los Angeles, former peers, legal analysts, and reporters, I became almost haunted by the reach this man had in California courtrooms. There’s even a harrowing excerpt from popular late-night Bravo show Watch What Happens Live, which featured embattled California governor Gavin Newsom acknowledging Girardi as one of his largest donors and most ardent supporters.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-