The Life and Death of Julia Pastrana, Bearded Woman on Parade

In Depth

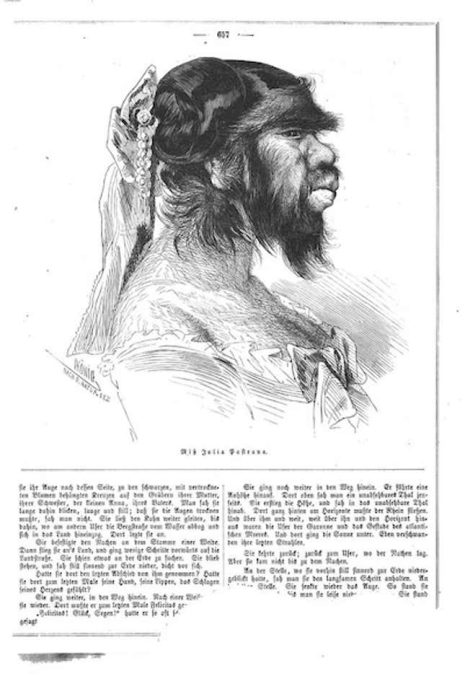

One of the best beards in history was grown by a woman named Julia Pastrana.

Records are blurry, but she was likely born in 1834 somewhere in Mexico, on the Western slopes of the Sierra Madre: a small, dark, hairy infant born to a poor Indian woman. Jan Bondeson writes in A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities, “According to the exaggerated accounts in the contemporary exhibition pamphlets, an Indian woman named Espinosa had become separated from her tribe in 1830, and was believed to have drowned. Six years later, however, some cowboys found her in a cave. She told them that she had been captured by a party of hostile Indians, who had imprisoned her in the cave, but no human beings could be found nearby.”

Espinosa had a child with her; she said the child wasn’t hers, but she cared for her and loved her. This child was christened Julia Pastrana. Years after this, Bondeson writes, Pastrana’s “supposed mother” died and the child was sent to a nearby city.

In an article for the Public Domain Review, Bess Lovejoy, author of Rest in Pieces: The Curious Fates of Famous Corpses, describes Julia Pastrana’s origins differently, and a little more clearly. She writes, “The local native tribes often blamed the naualli, a breed of shape-shifting werewolves, for stillbirths and deformities, and after seeing her daughter for the first time, Julia’s mother is said to have whispered their name. She fled her tribe—or was cast out—not long after.” Years later, according to Lovejoy, Pastrana and Espinosa (in this account, actually Julia’s mother) were found in a cave and taken to a city, where the child was placed in an orphanage. In both stories, she came out of the womb dark and hairy, with thick lips and wide ears. No one could explain it.

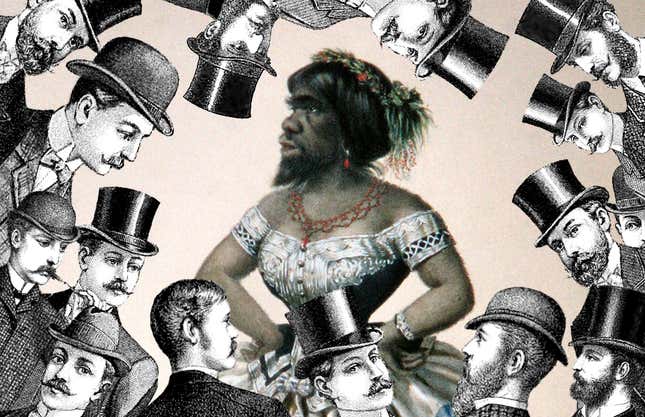

There are other stories about her origins, too, most a little more dubious and a lot more sinister. In 1854, when Pastrana went on tour, she was marketed both as a hybrid of monkey and man and also as a “bear woman.” A sensational pamphlet written by Pastrana’s manager and later husband, Theodore Lent, insinuated that Pastrana’s mother had gotten lost in the mountains and copulated with apes, baboons and bears. He wrote that she was “a hybrid, wherein the nature of woman predominates over the ourang-outang’s.”

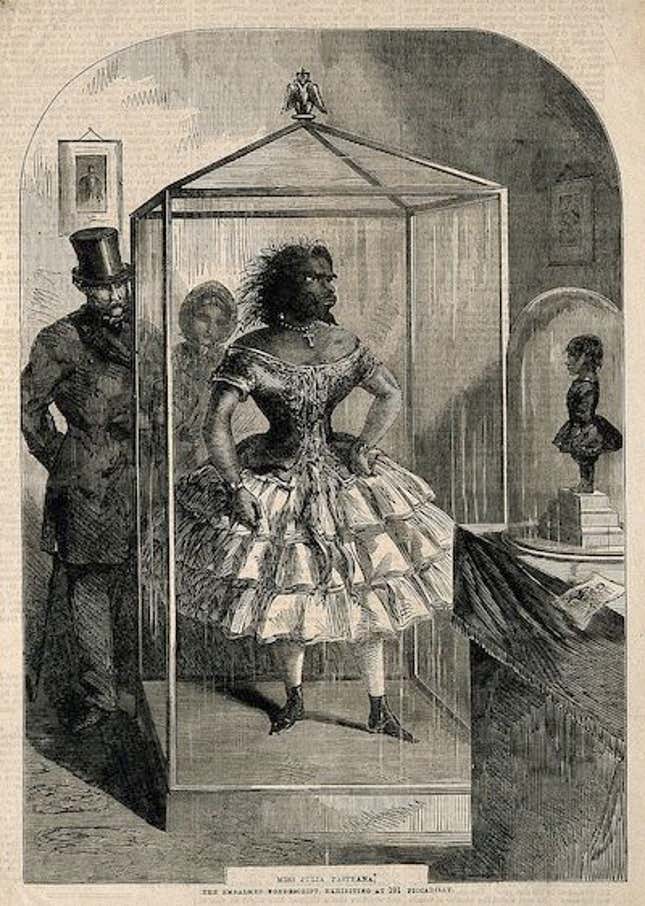

Funny words about your wife—but Theodore Lent was a particular type, anyway. He met Pastrana while she was touring the US, and when she died after six years of displaying her face and body’s thick, coarse black hair, Lent had her and their infant son stuffed, mounted and displayed like trophies. Later, he married another bearded lady, eventually displaying her alongside the stuffed corpse of his first wife and baby boy.

Before that, as a young woman, Pastrana had been taken in by the governor of the state of Sinaloa, who wanted to study her curious body. She was a servant girl for him and left in 1854 because of how horribly she was treated in the house. On her way back to her village, she met an American, M. Rates, who convinced her to tour with him.

I wonder how the American convinced her. By all accounts, Pastrana was a quiet and polite girl, very focused on propriety. Manners, maybe, were more controllable than the hair that sprang off her in coils. So, what did M. Rates say? Was it the money? The adventure? M. Rates was a proficient showman; he had experience dealing with “oddities” like Pastrana. Maybe he talked to her kindly—something few people had done, or ever would do.

At any rate, in America, she was a celebrity: shown to professors, danced at balls. Eventually she met up with Lent, who made his contract with Pastrana more permanent by marrying her. Lent essentially pimped his wife out: he subjected Pastrana to full medical examinations by the leading doctors in the towns they toured in. More than one source describes Pastrana as resistant to these examinations, during which she was often silent and Lent did the talking. Lovejoy records the words of the zoologist Francis Buckland, who examined Pastrana in 1857, as having an “exceedingly good figure” despite being “hideous.” Bondeson quotes a Dr. J.Z. Laurence, who wrote in The Lancet that with the exception of her palms and feet, she was hairy everywhere, “especially on those parts that are ordinarily covered with hairs in the male sex.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-