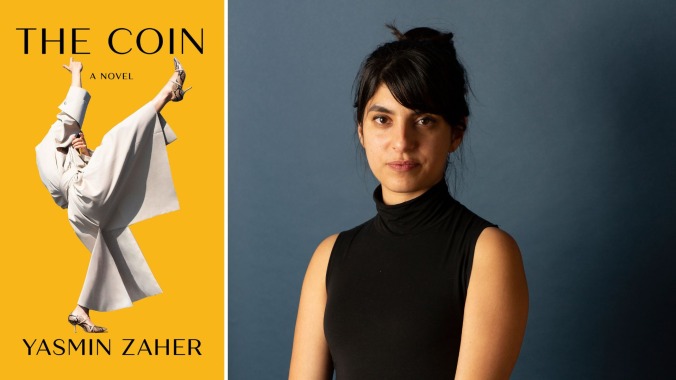

The Palestinian Protagonist of ‘The Coin’ Is Adrift in New York and Hustling Luxury-Hungry Americans

Yasmin Zaher's debut novel hides the ache for a lost homeland inside a surprisingly madcap narrative.

BooksEntertainment

The unnamed narrator of Yasmin Zaher’s astonishing debut, The Coin, is fierce, mercurial, dismissive, and unwittingly funny. Of a guy she is dating, she breezily remarks: “I wanted to be close to him, not in a dependent way, but in the way it’s nice to live near a convenience store.”

She teaches at a New York City school for underprivileged students, whom she oversees leniently, screening excerpts from Scent of a Woman and ignoring the syllabus. When she meets an enigmatic, dapper man known only as Trenchcoat, the two pivot to a side hustle reselling Birkin bags while wielding the narrator’s own inherited Birkin to herald her existent tastefulness.

Privately, she exhibits a fetish-level obsession with hygiene. During her at-home “CVS retreats,” she scrubs herself raw to be rid of what she sees as predatory urban filth. (But she is also aware of the absurdity of taking self-care to these obscene lengths: “Two thousand more years of snail cream and you will see a woman’s brain through her face.”)

Although outwardly young, sophisticated, and affluent, the narrator grapples with her identity: “I came from Palestine, which was neither a country nor the third world, it was its own thing,” she says. “I had chosen to stand on my own two feet and walk out of that crooked land.” Despite moving away from her roots, she doesn’t reject them: “I didn’t like looking white, because I’m not, I’m Arab.” In Paris, she explicitly “wrapped my Loro Piana scarf around my head and ears, not like Grace Kelly in a convertible but like a hijabi in Islamophobic France.” Her statelessness ultimately sets off a regressive unraveling.

Jezebel spoke to the Paris-based, Palestinian-born author, who got her MFA at The New School and has worked as a journalist for Haaretz, about maintaining America, the secrets writers keep, and feeling untethered. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

JEZEBEL: Tell me about developing this very compelling main character. She’s haughty and manipulative, but also tender with her students. How did you layer this complex person?

YASMIN ZAHER: I started by writing without inhibitions. The first layer was probably the chaotic layer—where things don’t really make sense, the strange connections between things that are based on very loose logic, the impulsive side of her, the improper side of her. As the story developed, I started to understand that Palestine is also a part of it, which wasn’t clear to me in the first few weeks or months of writing it. I started to round out the character in other places, maybe bring a little bit more compassion. But the first and most important layer for me was a character who was a little bit irrational.

I had tried writing two novels before, and it was too structured and boring. This novel I wrote just to see what I had inside. The way I wrote you could classify as binge writing: I wrote for 10 hours straight once a week. It took only a couple of months to finish the first draft. But then the first draft was so all-over-the-place that it took me six years to edit something that somebody would want to publish.

There’s an incredible pivot between the character’s “CVS retreats”—an extreme exhibition of control—to this complete deregulation at the end. How did that shift unspool?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-