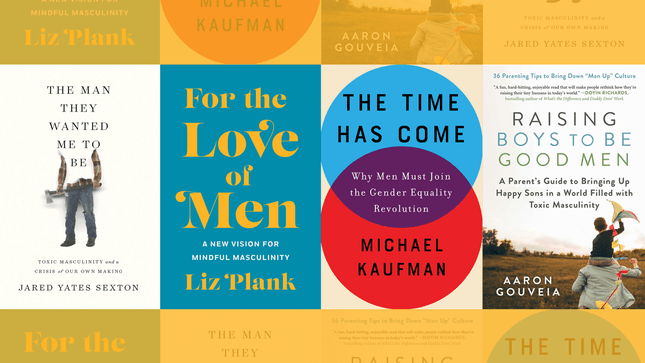

Graphic: Jezebel (Photos: Amazon)

Men are in crisis. The successes of women in the workplace have caused them confusion as to what telegraphs their strong manhood, if not being the primary breadwinner of their family. They’re becoming radicalized online in dark corners of the internet, where romantic rejection from girls can fester into plans for mass murder. And in a post-#MeToo world, they’re floundering, trying to figure out how to treat their women coworkers as equals, as the danger of being labeled a sexual harasser lurks around every corner.

The crisis that has befallen men is “toxic masculinity,” argues a burgeoning market of books that call on men to reflect on their own expressions of masculinity and potentially fix their brethren (or, at the very least, stop running around like a chicken with your head cut off because you can’t figure out what constitutes inappropriate touching). From books like activist Michael Kaufman’s The Time Has Come: Why Men Must Join the Gender Equality Revolution to parenting books like How to Raise a Boy: The Power of Connection to Build Good Men, the last few years have seen a boom in books that call on men to fight toxic masculinity. But in delineating a shiny new market of feminist-leaning resources for men among the decades of offerings for women already fighting for the cause, with an emphasis on reshaping masculinity for the better, these books ultimately play into the exact definitions of toxic masculinity they want to eliminate.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-