There's Nothing More American Than Religious Grandstanding

Latest

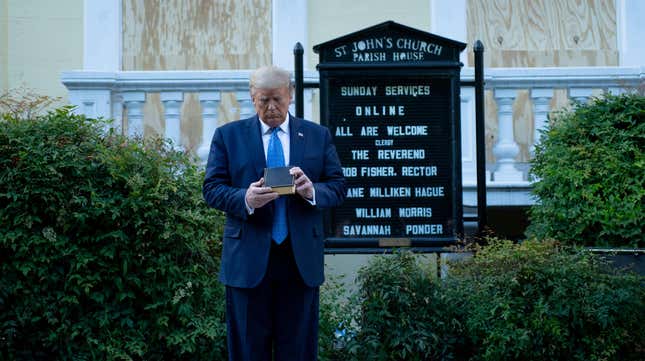

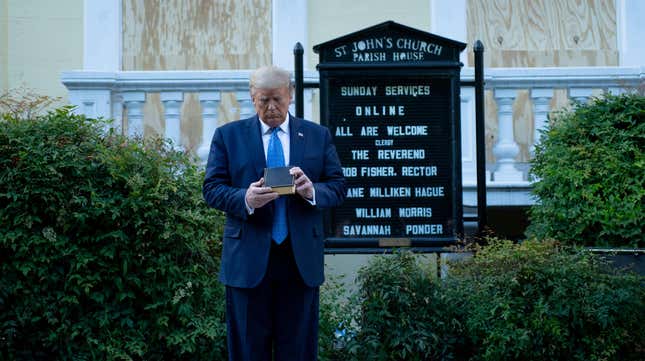

On June 1, police fired rubber bullets and tear gas into a crowd of peaceful protesters gathered in Washington D.C.’s Lafayette Park so that Donald Trump could clumsy fondle a Bible for the news cameras in front of the announcement board at St. John’s Episcopalian Church for a few moments. The next day, the president and first lady visited a monument dedicated to Pope John Paul II for even more stony-faced photo ops, prompting much hand-wringing about using religious backdrops for displays of dominance at a time of civic unrest. But what that hand-wringing ignores is the fact that Trump’s photo-ops are a magnified version of a political tradition older than America itself: creating the illusion of piety in service of gaining power.

In his 1962 lecture at Brown University, Eugene Rostow, the then-dean of Yale Law School, coined the term “ceremonial deism” to describe American religious gestures that were “so conventional and uncontroversial as to be constitutional.” In 1984, Supreme Court Justice William Brennan used the term again in Lynch v. Donnelly, a case involving the use of a manger scene on town property. In Brennan’s opinion, religious displays served secular, symbolic purposes so deeply ingrained in the fabric of Americana that they simply couldn’t be expressed without invoking religious symbolism. For example, phrases like “In God We Trust” work to “serve such wholly secular purposes as solemnizing public occasions, or inspiring commitment to meet some national challenge in a manner that simply could not be fully served in our culture if government were limited to purely nonreligious phrases.”

Photographs of presidents kneeling in prayer or standing in communion with religious leaders also act as signifiers that the politician pictured is a good person who follows the rules and guidelines for moral decency laid out in the Bible. Less than 24 hours after Trump brutalized protesters so he could hold a Bible upside down in front of an Episcopalian church, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi was whipping out her own Bible at a press conference, clumsily (and selectively) quoting from Ecclesiastes in order to pay lip service to the idea of the nation “healing” from the police violence that sparked a week of protests and continues as police shoot, tear gas, and beat unarmed protesters around the country. Pelosi’s announcement of plans for change was flimsy, but brandishing the Bible, she gave the impression that she answers to a higher authority than Trump. On June 1, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden was also photographed at a church, kneeling with black religious leaders in Wilmington, Delaware; the photographs seemingly meant to show Democratic voters that he is on the side of both God and the black community in this time of protest.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-