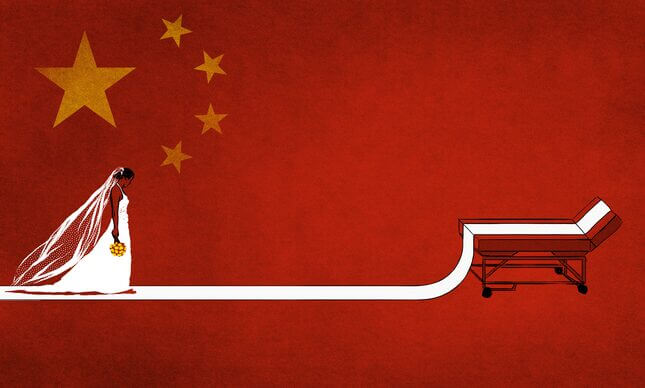

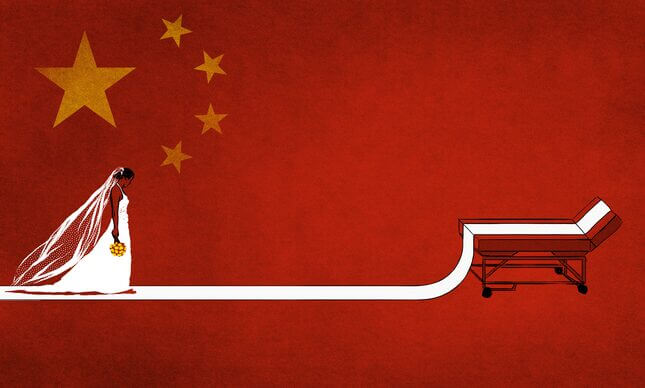

Why Is It So Hard for Unmarried Women in China to Go See a Gynecologist?

Latest

The first time Crystal Wang had a gynecological exam was at a large medical center in the central business district of Beijing. When she arrived at the examination area, she was taken aback by a bold red sign that said 处女不能检查, or “virgins may not be examined.”

Crystal, who was 22 at the time, was not a virgin, but she was also unmarried—a combination she didn’t expect would go over well with hospital authorities. “I lied and ticked the married box on the personal information forms,” she said.

Throughout the course of Crystal’s examination, the doctor and nurses were extremely kind. They asked her when she planned to have a baby, and although there was a huge line of women outside waiting to be examined, they answered all of her questions thoroughly.

As she left the exam room, she noticed that another young woman who had been waiting was getting turned away. Unlike Crystal, the woman had indicated on her form that she was not married; after telling the nurse that she was sexually active and requesting an exam, she was begrudgingly given a number and directed to the back of the line.

“They were treating her like trash,” Crystal said. “They were forcing her to make very personal admissions in public and clearly not giving her the same respect or attention they had given me.”

When Crystal got home later that evening, the first thing she did was very carefully hide all the paper traces of her doctor’s visit so that her mother wouldn’t find them. “She would go bonkers,” said Crystal, explaining that for unmarried women in China—especially those who still live with their parents—a visit to the gynecologist is a scarlet letter of sorts. Pap smears and pelvic exams are considered routine for women who are married, but can be a flagrant violation of propriety for everyone else.

As Crystal explained, and several other Chinese women have corroborated, there are two main ways to have a gynecological exam in China. You can go to a large women’s hospital and simply pay for the exam out of pocket (starting at around USD $30, depending on the hospital), or you can have the exam at a smaller facility as part of an annual health check package offered by your employer. These exams take place at checkup centers that are usually staffed by retired doctors or those seeking to make a bit of extra money on the side, and are essentially considered a workplace perk.

26-year-old journalist Xinyuan Yu’s first visit to the gynecologist took place on one of these employer-provided health checks. Unaware that her marital status would determine which examinations she would be entitled to, she filled out the forms truthfully, and checked the box to indicate that she was unmarried. As she hopped onto the examination circuit and began going from exam room to exam room as if on one large production line, she realized that there was one room she hadn’t been assigned to, and approached the nurse at the door to ask why. “Are you married?” asked the nurse. “No,” said Xinyan. She was promptly shooed away without explanation.

Startled, she set off to have the rest of her examinations. A blood test, eye exam, pelvic sonogram, and ear nose and throat probe later, she returned to the room where a cantankerous nurse was still standing guard.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-