'You're Not a Racist and Neither Am I': The Former Feminist Who Turned to White Supremacy

In Depth

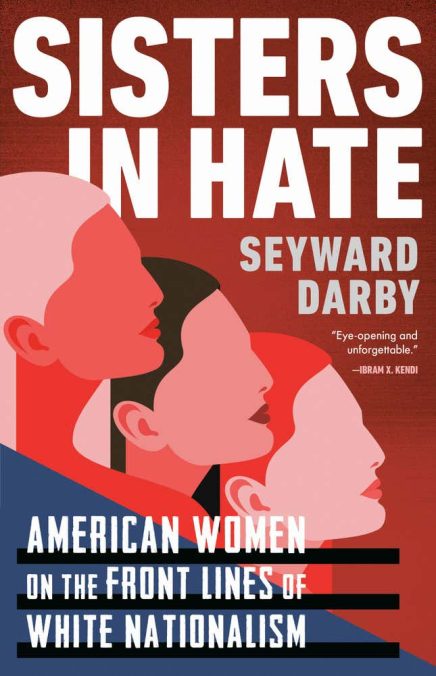

Illustration: Angelica Alzona

As viral content goes, the photograph was a blockbuster, accumulating more than ten million likes and three hundred thousand comments on Instagram. First published on July 13, 2017, it showed music megastar Beyoncé cradling her one-month-old twins against her naked torso, standing beachside in front of an arch laced with lush flower blossoms. A pale teal veil was affixed to her rippling blond hair, and a sheer purple robe cascaded from her shoulders to her bare feet. Her head was tilted so that her face caught the sunlight beaming down from the clear blue sky. In the distance was a blurry horizon where ocean met air.

The image was a visual echo of Beyoncé’s famous pregnancy photos, released earlier the same year. The aesthetic was inspired by art dating back centuries: Beyoncé was Raphael’s Madonna, Botticelli’s Venus, the Virgin of Guadalupe. She was a Black woman inserting herself into a canon that so rarely depicted figures of color, much less glorified them. “She appears as not one but many women—or, instead, maybe the universal woman and mother,” an art history professor at New York University told Harper’s Bazaar.

When she saw the photo, Ayla Stewart had a different take. She wondered why people had such reverence for Beyoncé, the kind Ayla believed should be reserved for the divine. A devoutly Christian mother of six with a round, dimpled face and wide blue eyes, Ayla decided to denounce what she saw as idolatry. As Beyoncé’s image ricocheted around the internet, Ayla screen-grabbed it. She juxtaposed the photo with a painting of the Virgin Mary and an infant Jesus, encircled by gilded haloes. Ayla captioned the side-by-side comparison “Tubillardine [sic] Whiskey (1952) vs. Kool-Aid.” Mary was the vintage; Beyoncé was the fake stuff.

Ayla shared the meme on Twitter, where she kept an account under the name Wife with a Purpose. Reactions were swift, and some were furious. “Girl, fuck you,” one Twitter user wrote. “I haven’t beat anyone up all year so I’m ready to fight.” The website Bossip included Ayla in a roundup of “mediocre mayo packets who spent their whole entire payday splattering not-very-subtle racism all over Al Gore’s world wide web” because they didn’t like Beyoncé’s photo. In Ayla’s case, the racism was in the association between Kool-Aid and African Americans, a long-standing stereotype implying that Black people enjoy—or can only afford—cheap, childish, and unhealthy things.

Ayla had established herself as one of the internet’s most vocal proponents of tradlife, short for “traditional lifestyle,” a movement advocating retrograde values and hierarchies between men and women, states and citizens, God and humankind. She believed that white, Christian, heterosexual people, who represented all that was natural and good in America, were under threat from immigrants, feminists, liberals, and LGBTQ people. “Tired,” Ayla once typed in red letters over an Instagram image of two transgender women of color; “woke,” she wrote over an adjoining photograph of a large white family.

Ayla always insisted that she loved all God’s children and even prayed for the ones who didn’t agree with her worldview. It wasn’t racist, she said, to believe that people should stay in their cultural lanes and within their national borders. A few months before the Beyoncé controversy, just after Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election, Ayla had tweeted another photographic comparison—her favorite type of meme, it seemed—of a Black woman and a white one. The Black woman wore a turban and dress cut from a colorful wax print. The white woman’s blond hair was twisted into a long, thick braid that poured over her peasant blouse. The images were supposed to represent pan-African and pan-European aesthetics. “You preserve your culture and people and I’ll preserve mine,” Ayla wrote beneath the images. “You’re not racist and neither am I.”

Invoking ideals of femininity rooted in whiteness—Beyoncé need not apply—Ayla compared the America she yearned for to the world of Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield, the twin teenage protagonists created by young-adult author Francine Pascal. “If things stay on track,” Ayla warned on Instagram, “one day, Sweet Valley Twins books will be illegal for featuring two blond, straight, skinny, girls, whose parents were still married and live in a place called Sweet Valley, where there were no mall shootings, no illegals, no homosexuals*, no transgenders, no Muslims, everyone spoke English and the internet, blissfully, didn’t exist. A land where girls still baked cookies for the boys and mom’s prioritized their homes.”

Ayla didn’t hesitate to malign critics of tradlife—or, really, anyone who refused to embrace the culture. If they didn’t model their lives on the values of the past, they were lazy, or worse. “None of this degenerate behavior should we accept as normal practice,” Ayla once said. “When people speak out against it, we shouldn’t label them phobics or try to shame them for speaking out in favor of normal, healthy standards.” In her mind, the people who agreed with her were courageous.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-