A Short, Freakish History of Mothers Harming Their Children For Money

Latest

At the end of the sixteenth century, there was an infant in France with an excess of skin on its head. The parents of the child were poor and carried their infant from town to town, putting him on display for profit. When they reached Paris, a magistrate questioned them, suspecting the pair of fraud. The parents rolled, telling a tale even worse than the public had suspected.

Fabricus Hildanus, father of German surgery, describes their confession: “They had cut the skin of the infant’s head by making a little hole about the crown to the very muscles and by that very hold (putting in a reed between the skin and the muscles) had blown into it, and by degrees, within some months (by continually puffing into it) the skin of the infant’s head was extended to that altitude and that they did expose it to all here and about France to get money thereby.”

As punishment, the parents were put to death.

Maiming and manipulating children for profit is an old profession. And in an age when medicine was often more guesswork than scientific process, the line between the monsters that were born and the monsters that were created was often very thin. Many modern researchers have a hard time separating the facts from the fantasies.

For example, dwarfing children through malnourishment in order to put them on display was so common that, in her history of dwarfism, Dr. Betty Adelson dismisses some ancient tales of dwarves out of hand. This practice was as old as ancient Rome—where there’s a record of owners intentionally malnourishing a slave child in order to sell him as a dwarf for a higher price.

Of course, that’s not the only way of hurting a child for money. In London, in the 1720s, a child with “Jehovah Elohim” written on his eyes was displayed and heralded as the Messiah—until someone revealed that his parents had put small pieces of engraved glass over his eyes. 16th century physician Ambrose Pare writes in On Monsters and Marvels that some counterfeiters have taken children and “broken their legs, poked out their eyes, cut off their tongues, pressed upon and carved their chests saying lightening bruised them thus…”

This is not—and was never—good parenting. Parents are supposed to give their bodies to their children, not use their children’s bodies for profit. This ideal is especially true for women, and is so powerful that the Brothers Grimm edited bad mothers out of their stories. For example, in Jack Zipes’ translation of the first edition of the Grimm’s work, Hansel and Gretel are sent off to die by their own mother, not an unfeeling stepmother. But the Grimm brothers changed this. Their nervous editing seems to beg the question: no real mother would knowingly be cruel to her children, would she? No “real mother” would ever harm her child.

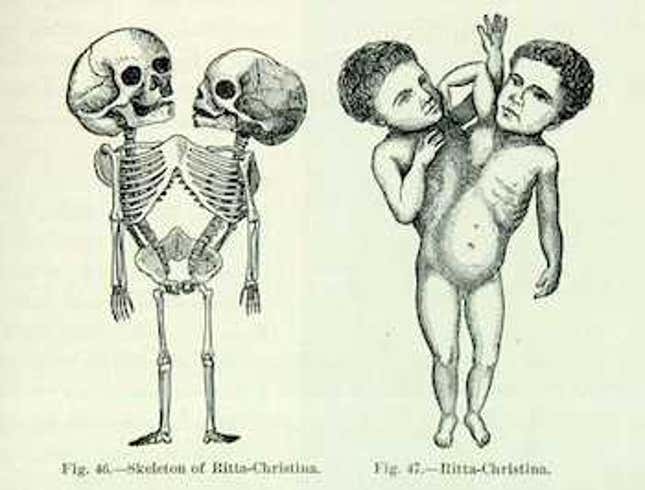

Along with the parents who deformed their children for profit, there were the parents who would use their children’s existing deformities and use their own personal gain. In 1829, a pair of conjoined twins named Ritta-Cristina were put on display in Paris. The girls were only six or seven months old. They had been born to poor parents in Sardinia, who had eight other children. Perhaps encouraged by the doctors or impressed with the fanfare surrounding their daughters, the parents decided to take their babies on tour. But, in Paris, the authorities thought showing the girls off was vulgar. So they shut the show down.

Destitute and desperate, Ritta-Christina’s parents started showing their daughters in a run-down house. They couldn’t afford coal or firewood and Ritta developed bronchitis. While Ritta coughed and struggled to breathe, her sister, joined to her from the rib cage down, laughed and played. The parents were penniless, and Ritta died three days after she became ill. At the moment that Ritta breathed her last, Christina, who had been playing with her mother’s hand, cried out and followed her sister into death.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-