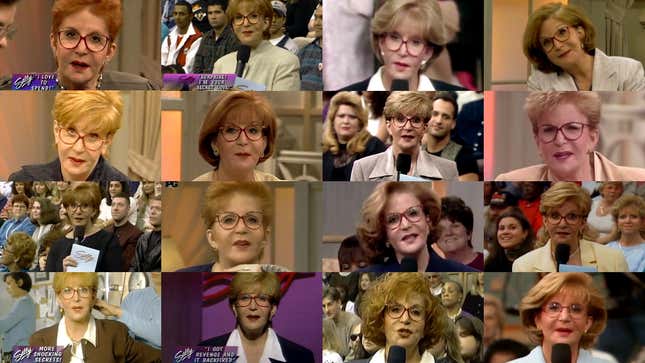

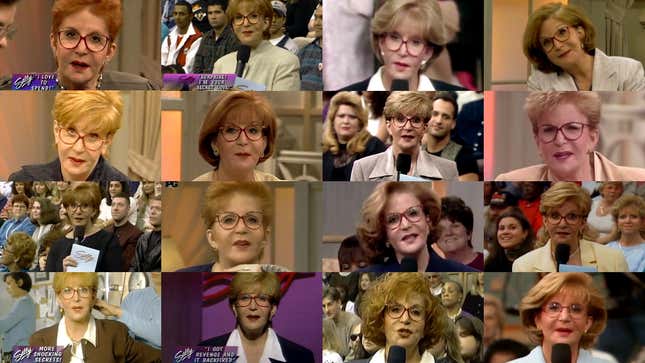

For some reason, there are 233 episodes of the classic daytime talk show Sally (originally titled The Sally Jessy Raphaël Show) streaming amongst episodes of Jerry Springer, Maury, and Divorce Court on the trash-TV platform Nosey. On that free streamer, Sally is virtually the only show of its kind: A general interest talk show whose guests and topics are (mostly) plausible and presented with no threat of the entire operation devolving into professional wrestling.

Though most of these Sally episodes seem to span the years of 1995 to 1997, they retain the essence of ’80s talk shows. While frequently tense and not at all short on drama, they remain sick-day soothing, a portal to a time when things were simpler and when people went after mic-drop clout by telling others exactly what they thought of them to their faces.

Watching a handful of Sally episodes recently, it struck me how efficient a vehicle the now outmoded talk show format once was. You can detect the roots of so much of what came to flourish in pop culture. The salacious daytime talk show was the missing link between the sideshow of old and reality TV, for offering the opportunity to gawk at humanity without adulteration. That the episodes are largely populated by inexperts who pull no punches in pontificating on whatever the fuck, whether it’s based in reality or not, makes the format a precursor to podcasting. Here’s one of the subjects of “I’m Proud That I Date Married Men” claiming that one incentive of doing so is that it allows her to find partners with bigger penises:

The call-response format—that is, after the guests laid out their identities as they applied to the topic of the show, the audience lined up to have their say—was a nascent and IRL version of Twitter discourse. People brutally weighed in on each other, seemingly motivated as much by self-expression as the applause that dunking on someone would elicit. It’s difficult to imagine a contemporary entertainment journalist going as hard on Robin Quivers, Howard Stern’s co-host who was criticized for standing by while Stern made racist jokes in his early years on air, as the audience member does here:

The palpable pride of so many guests in sharing that thing about them that makes them special enough to discuss on television is not unlike that which frequently evinced during the golden age of the personal essay on blogs in the early 2010s. Both the talk show and the personal essay cut to and then through the heart of Middle America, operating under the premise that we all have something special about us, even the most “normal”-seeming members of society. You can even see the origins of how so-called “identity politics” came to play themselves out online: guests define themselves per the day’s topic, they defend said identity, and they argue why it’s important for you to know this. There’s also a lot of subsequent, “You don’t know me, you can’t judge me!”-style indignance when they fail to persuade and the audience registers its disapproval.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-