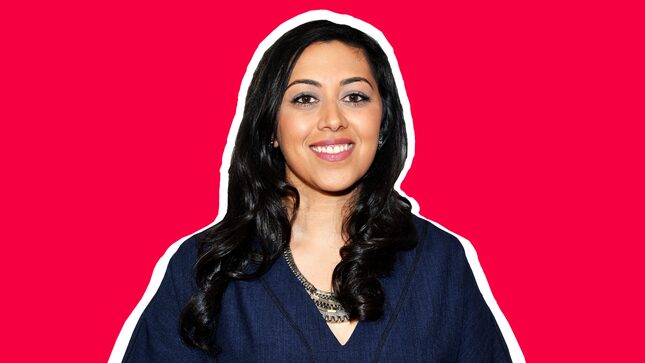

Graphic: Jezebel (Photos: Noam Galai/Getty Images)

In May, after binge-watching Netflix’s Love Is Blind with equal parts morbid fascination and disbelief, it felt inevitable that the streaming service would eventually serve a reality show about arranged marriages. I hoped it wouldn’t be—as I jokingly tweeted—Love Is Arranged, a show about judgmental Indian aunties pushing a group of wayward American millennials to find life partners on a tropical island. Lo and behold, three months later, Netflix debuted Indian Matchmaking. The original series follows Mumbai-based matchmaker Sima Taparia as she meets Indian millennials and their families who are looking for life partners in both India and America.

Thankfully, it’s not the exoticizing, over-the-top production that I had fearfully anticipated. This is because the show was pitched and created by Oscar-nominated director Smriti Mundhra, the Indian American woman behind 2017 documentary A Suitable Girl, which offered a nuanced look at arranged marriages in India today and the disproportionate impact on the women who enter them. (I wrote about how the film prompted me to reflect on my own upbringing and understanding of the method by which most of my family members have married). Under Mundhra’s careful eye, Indian Matchmaking is as binge-able as any popular dating reality show on TV, while still retaining authenticity. Think Dating Around, except everyone is of Indian ethnicity, we follow their journeys before and after the first date, and we witness the intricate process—which includes interviews with their families, matchmakers, astrologers, and resume-like documents called Biodatas—to set them up.

Each of Taparia’s clients faces a set of challenges in finding the right partner. Ankita, a Mumbai-based entrepreneur, seeks a man who will see her as a full equal. Nadia faces discrimination within the Indian American community because she is Guyanese Indian. Vyasar, a guidance counselor in Austin, Texas, fears judgment because he is estranged from his abusive father. Some of the episodes are bookended with delightful conversations between older South Asian couples who reminisce over their long-lasting arranged partnerships, creating an engaging show that, as a first-generation Indian American woman, I could comfortably binge-watch with both my mother or my white friends without feeling the need to explain or translate.

The show attempts to reclaim a cultural tradition in South Asia that has long been misrepresented in the West, but in doing so, is also burdened by a misperception, or even a demand, that it speaks for an entire subcontinent of people. Instead, it offers a window into the psyche of families that enjoy a substantial amount of privilege: Taparia’s featured clients range from upper-middle-class to the ultra-rich, and all are middle and upper-caste Hindu and Sikh Indians seeking heterosexual relationships. While their reasons for seeking a matchmaker are diverse and varied—some insist that it’s time for their children to marry, whereas in other families, children who are unsatisfied by dating initiate the process—the process also reveals how, in their quest for a “good” match, cultural and caste-based biases are baked into vetting potential partners.

Mundhra anticipates that the show will prompt difficult conversations and criticisms within, and about, the Indian American community. “I’m thrilled with the praise, but I’m ready for the critique, too,” she says. “I want the show to start a conversation. I want, for me as a creator, to be held accountable by my community, and I want the opportunity to have a season two to push these conversations even further.” Ahead of its debut, I spoke to Mundhra about the series, her experience pitching the show, and what conversations she hopes it inspires.

JEZEBEL: In A Suitable Girl, you explored arranged marriages in India. Aside from the obvious shared theme, are these two works connected in any way?

SMRITI MUNDHRA: Sima was my matchmaker, and she was a very well-known person in our community in India. I was so captivated by her because she was such an incredible character. She’s almost like made-for-TV. We got to touch a little bit on that in A Suitable Girl because the film was about the perspective of the young women—and Sima’s daughter’s journey–but there was this whole other world that we didn’t get that much into in A Suitable Girl, which was the business of matchmaking.

Far more people are going to see this show than have seen my film. That’s an opportunity to talk about the great things about our culture and our traditions, but also some of the problematic things. As South Asians and as Indians, what is our relationship with marriage in this day and age? How does it evolve and what parts of it should we preserve? That’s what excited me about it, that we get to talk about this in this package of this super fun, appealing, widely available piece of pop culture. In the process of making this show, I really recognized the power of mainstream shows and films to smash stereotypes. I think a lot of people have a lot of stereotypes about arranged marriage, and hopefully, this show breaks through that and shows how varied and adaptable it can be, but also forces a conversation around some of the things that are long overdue for change.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-