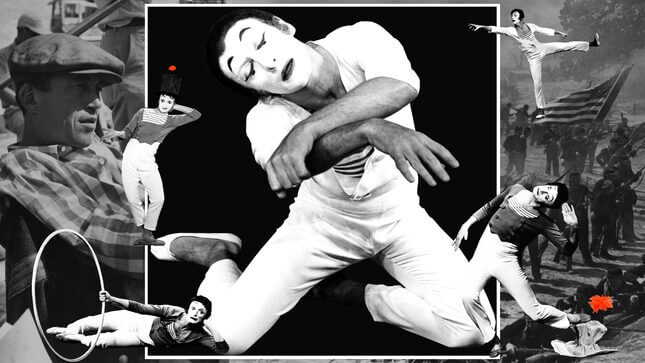

Illustration: Elena Scotti/GO Media (Photos: Getty)

“Marcel Marceau’s first wife divorced him in 1958,” Shawn Wen writes of the famous mime. “She said he would not speak to her for days on end. She called it mental cruelty. He called it rehearsal.”

This anecdote arrives early in A Twenty Minute Silence Followed by Applause, Wen’s 2017 book-length essay on Marceau’s art and life. Wen twines them on the page—art, life—as they’re twined in reality: to disentangle is to lie. How could we possibly separate the man from the work—this man from this work, when it is not merely made by him but made of him: his face, his limbs? “The body was their text,” Wen writes of the School of Dramatic Art in Paris where Marceau trained after World War II to become a mime. Marceau’s body was his language; his body was his clay; his body was his canvas and his instrument and his philosophy. But as with any artist elevated (or reduced) to celebrity, it becomes hard to identify where the rehearsal stops and the performance begins.

Of course, that’s precisely the place that piques the interest of the voyeur. A Twenty Minute Silence teases in this direction: Marceau’s daughter is quoted; his wives are summarized; we are told that his brother was a leader in the French Resistance, that his father died at Auschwitz. Wen points out that Marceau’s given surname, Mangel, means “lack” or “deficiency”—the temptation must be great, when writing about mime, to fill the silence. Connected as they are, however, Wen’s nods to the incomparable life don’t come at the expense of the even more remarkable, if less articulable, art. With great rigor and a feeling patience, she writes into the empty space created by Marceau’s wheeling arms, his gesturing eyes, his open and soundless mouth. (As the art critic Peter Schjeldahl says, “I like the discipline of writing about mute things. It feels like honest work.”)

Biographical facts and quotes are spliced by scenes starring Marceau’s iconic creation, the white-faced, striped-shirted character Bip: Bip dresses for a party; Bip ducks in the trenches. Wen’s language is plain and unadorned as the stage; she does not qualify the “bow tie” and “jacket,” the “canteen” and “comrade,” with their obvious falsity. Only when we might mistake the object for a part of the theater’s architecture does she highlight the illusion: playing a drunken partygoer, Marceau “hangs on to invisible walls for balance.”

How does a man move? How does an author convey movement in the two fixed dimensions of prose?

How does a man move? How does an author convey movement in the two fixed dimensions of prose? If the man is Marceau or the author is Wen, the answer is the same: with unerring grace. Wen writes in a slim, sculpted style; she cuts her sentences, occasionally, into the lines of a poem. (This is hardly necessary, but it doesn’t bother.) No approach can be ruled out, when trying to articulate a viewing experience that is, by definition, resistant to language. As Marceau says, “Mime can do things that words cannot.”

Words can do things that mime cannot, too, but Wen largely rejects interiority, that advantage of the written word over visual art, film, theater, and dance: the mind on display in Wen’s essay is not her own. She can access Marceau’s singular mind only through its physical effects: the body attached, its movement, what it says or doesn’t say, what it does. Wen follows Marceau through his performances with forensic attention. “Bip’s gaze populates the empty stage with a crowd,” she writes. “A ghosted landscape rises up wherever his fingers point.”

I was reminded of this bodily observation when reading Picture, Lillian Ross’s 1952 work of reportage on the making of John Huston’s The Red Badge of Courage. “He has a theatrical way of inflecting his voice that can give a commonplace query a rich and melodramatic intensity,” Ross writes. “He made the most of every syllable, so that it seemed at that moment to lie under his patent and have some special urgency.” Ross delineates and categorizes the movements of Huston’s speech as precisely as Wen traces those of Marceau’s fingers and feet: intentional, multivalent, ripe for interpretation. Writing 65 years apart, Wen and Ross couldn’t possess more divergent styles, but they share an ambitious goal: to recreate on the page what is inherently, flamboyantly unbound.

Ross has an easier time of it: her subjects are not mute. Huston talks, his producer Gottfried Reinhardt talks, studio bigwigs and critics and actors and hangers-on talk and talk and talk. Dialogue runs roughshod over the pages of Picture; the journalist’s glee at good copy sparks audibly from Ross’s electric sentences, phrases, even fragments. “‘Well!’” she quotes Huston saying, and adds an aside: “He made the word expand into a major pronouncement.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-