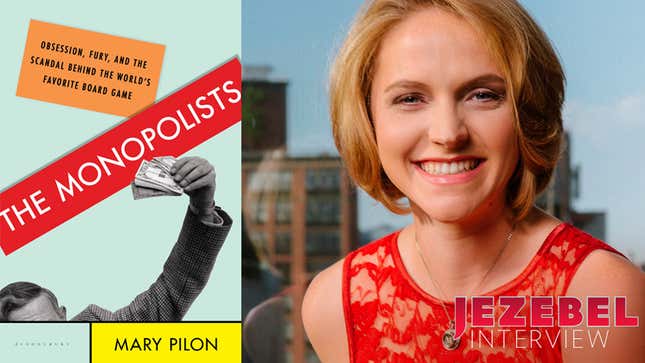

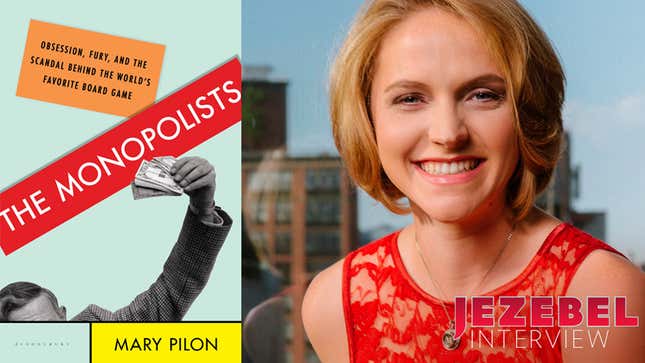

How Author Mary Pilon Found the Woman Inventor of What Became Monopoly

In Depth

We’ve all heard the story of how Monopoly was invented in the depths of the Great Depression by Charles Darrow, a man down on his luck—until he started tinkering with a board game inspired by happier days in Atlantic City…

Sadly, it’s bunk. But as Mary Pilon’s The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind America’s Favorite Board Game details, the truth is even more fascinating.

You see, what would evolve into Monopoly was actually invented in 1903 as the Landlord’s Game. Its author was a woman, Lizzie Magie, who wanted to protest monopolies and promote the economic theories of “single tax” advocate Henry George (who held that nothing but property should be taxed, the idea being land should be a communal good but anything you create is yours). The game would spread across the Northeast and Midwest in university towns and other liberal enclaves, including the Quaker community of Atlantic City, who introduced their own modifications. One person would teach another on handmade boards, until finally somebody taught Darrow—who was broke and at his wit’s end, trying to figure out how to get the expensive care his disabled son needed. He enlisted a talented illustrator to create the board you’d recognize today and sold the whole thing to Parker Brothers.

Pilon interweaves the story of the game’s origins with that of Ralph Anspach, a professor who—not knowing the first thing about Lizzie Magie—invented his own political, educational board game and named it Anti-Monopoly. Then came the cease and desist letter from Parker Brothers, which got Anspach digging.

I chatted with Pilon about how she uncovered all this, why we don’t remember Magie and the sheer volume of shit you just can’t find on Wikipedia.

How did you come to the project? How did the book happen?

It was a total accident. This was in 2009, 2010; I was writing about business at the Wall Street Journal, and I had grown up loving games, puzzles, all of that, and history. I had this throwaway line in a totally unrelated story about Monopoly being invented during the Great Depression. And I thought, well, everybody knows it was invented during the Great Depression. So I was looking around and looking around, and it wasn’t adding up and I was totally frustrated. I’m writing about derivatives and I can’t get the Monopoly story right? What’s wrong with me?

So I came across Ralph Anspach and his lawsuit. I’m an advocate of the reporter trick of calling counterparties in lawsuits, because often if you sue somebody or you’ve been sued by somebody, you do a lot of research. I contacted Ralph on a whim and I said, “Hey, I know this is crazy, but I’m a reporter at the Journal and I’m just trying to find out the truth about Monopoly.” He wrote back right away. He started talking about his lawsuit and Lizzie and what happened in the 30s with Darrow. And I just was like, Oh my gosh. So I completely stumbled into this by accident.

I ended up writing the original story for the Journal about Ralph and his lawsuit. And then usually, when you’re done with a story you’re so sick of it, but this time I had more questions. I wanted to know more about who this woman was, I wanted to know more about what happened. I just kept reporting out what eventually became the book proposal and then eventually the book.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-